What Did Japan Whisper in 1992 That America Is Finally Ready to Hear?

Long buried in the soft static of forgotten cinema, Bye Bye Love resurfaces under Kani’s wing with U.S. distribution rights—and suddenly, everyone’s listening. But why now?

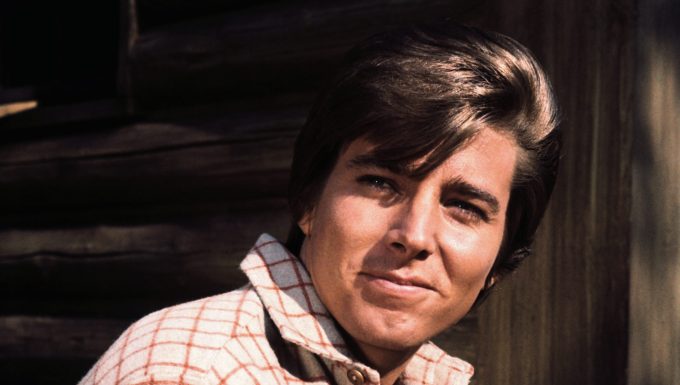

A boy with bleached hair leans against the frame of a cigarette-scarred doorway. His shirt is wrinkled. His gaze, razor-thin. The light is flickering—not from a storm, but from the kind of neon that hums like a memory trying to surface. Bye Bye Love doesn’t begin with drama. It begins with ache.

And for thirty years, that ache sat in silence. Until now. Kani, the quietly radical distributor of underseen world cinema, has acquired U.S. rights to this long-forgotten Japanese queer film—a choice that feels less like a revival and more like an omen. What does it say about America that it’s just now ready for a story told in 1992?

Soft Power, Sharp Silence

There’s nothing loud about Bye Bye Love. It never preaches. It never shouts. It just waits—for the viewer, for the moment, for recognition. The film sways like a paper lantern in windless air: intimate, undecorated, and often unbearably close. It’s not about being queer in Tokyo. It’s about being lonely in your skin, and watching desire form like condensation on the edge of someone else’s glass.

That, perhaps, is the disquieting brilliance of it. The queerness isn’t spectacle—it’s shadow. It’s absence. It’s the space between boys who don’t quite touch. A Kani rep noted, “This isn’t a coming-out film. It’s a coming-apart one.” And in that fracture, there’s something eerily modern. Gen Z calls it “vibes.” Millennials might call it “emotional minimalism.” The truth? It’s what loneliness looks like when you don’t have the words—or permission—to name it.

Why Now? Why Us?

America’s cinematic appetite has shifted. Audiences, once addicted to the crash-bang clarity of identity politics in film, now want ambiguity. Tension. Films that feel like secrets rather than statements. Bye Bye Love is the secret whispered in a crowded room—and Kani, perhaps, is betting we’ve finally learned how to listen.

There’s a quiet political gesture in acquiring this film now. In a year when anti-queer legislation is snaking through headlines, and Asian representation is either hyper-stylized or erased entirely, Kani is offering a third path: intimacy. No declarations. Just bodies in space. Just breath. Just longing. The message, if there is one, is simple: you don’t need a megaphone when the silence is already loud.

So maybe the real question isn’t “Why did it take so long?” but “What else have we been too loud to hear?”

Back in that doorway, the boy lights another cigarette. He doesn’t look up. He doesn’t need to. He knows now—we’re watching.

Explore more

When Are the Oscars 2026? Date of the Academy Awards – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images The Oscars are officially on the...

Where Is Lawrence Jones on ‘Fox & Friends’? Health Update Amid Hiatus – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images Fans of Lawrence Jones, a Fox & Friends...

Who Is Lexi Minetree? 5 Things to Know About the ‘Elle’ Series Actress – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images for Hello Sunshine Lexi Minetree plays...

Release Date, Cast & Updates on ‘Elle’ – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Courtesy of Prime Video What, like producing a...

Leave a comment