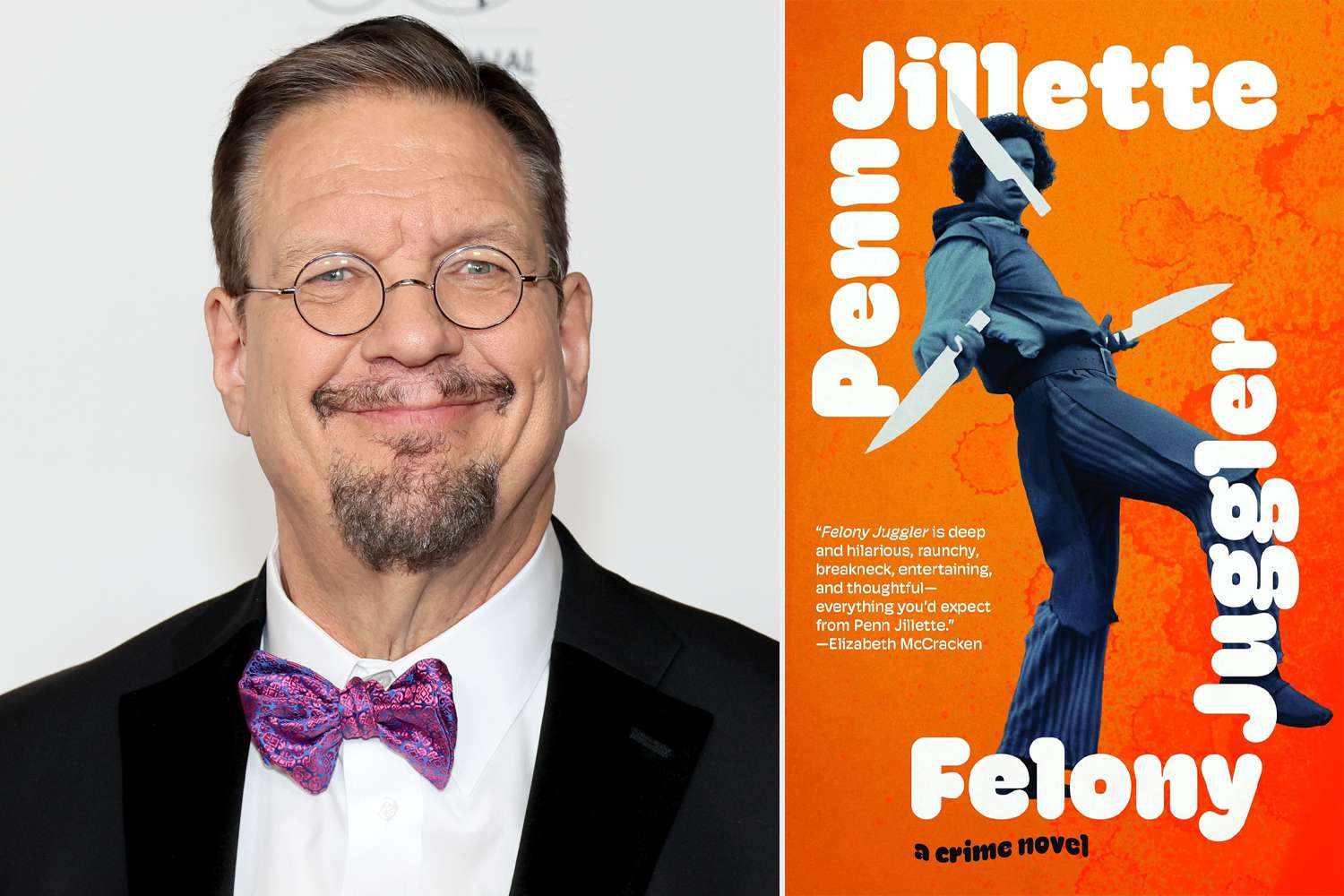

The Trick Penn Jillette Doesn’t Want You to Solve

Penn Jillette’s Felony Juggler claims to be “mostly true”—but the real illusion might be how we mistake performance for confession.

Dia Dipasupil/Getty; Akashic Books, Ltd.

The first lie is that we expect the truth. The second is that we believe it when the storyteller warns us it’s “mostly true.” And Penn Jillette, magician, provocateur, and master of sleight-of-thought, has made a career out of dressing his truths in just enough fiction to make them irresistible. His new book Felony Juggler is the latest act—a genre-defying cocktail of memoir, mischief, and moral ambiguity that dares you to believe what you know is probably false.

What Jillette offers is not a retelling—it’s a performance. The prose is sharp, the humor savage, the details oddly specific. And then there’s that chapter. The one he now admits is “embellished.” But embellished how? And why that chapter in particular? In a book filled with criminal near-misses, childhood curses, and confessions that could dent a polygraph, the part that’s not true says more than the parts that are. Which is the point. Or the distraction.

The Seduction of the Semi-True

We are living in an era addicted to the semi-autobiographical. Memoir has become mood board, confessional booth, and performance art all at once. We don’t want facts—we want stylized trauma, curated chaos, and irony wrapped in paperback. Jillette, as ever, is ahead of the curve. He knows the trick isn’t in hiding the lie—it’s in telling you it’s there and daring you to look for it anyway.

In one chapter, he writes: “There are truths too boring to remember and lies too good to forget.” It feels like a thesis wrapped in punchline. And perhaps a warning. His career has always existed in the grey space between belief and disbelief. Now, his legacy might too. Because what do we do with stories that are almost true? Do they matter less—or far more?

When Confession Becomes Camouflage

The public loves a magician’s memoir for the same reason it loves a scandal: it wants to peek behind the curtain. But Jillette, with his trademark bravado, has stitched a second curtain behind the first. Felony Juggler isn’t just a story. It’s a trapdoor. The reader tumbles through chapters, unsure if they’re laughing at a punchline or a piece of evidence.

And still, the most chilling element isn’t the crime—it’s the casualness. The way charm masks cruelty, the way memory morphs under spotlight. If Jillette told the truth where it mattered, he also hid the fiction where it stings. He’s not just playing with narrative. He’s playing with culpability.

So we ask again—what, exactly, is the lie? And why did he need to tell it?

Explore more

When “107 Days” Meets Outcry: Harris’s Book Tour Interrupted

The microphone crackled to life, and before Harris could finish her opening...

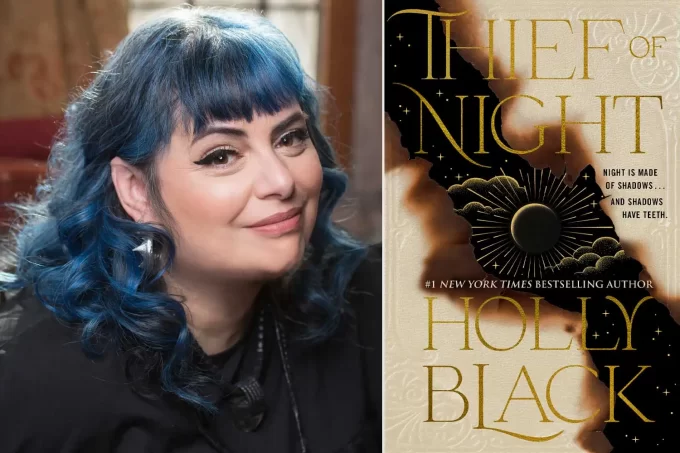

Whispers in the Shadows: Why Holly Black’s Sequel Is a Dark Invitation We Can’t Ignore

The night isn’t just dark—it’s ravenous, greedy, and it’s coming for you....

Why Stephenie Meyer’s Regret About Edward Changes Everything You Thought You Knew

The moment Stephenie Meyer admitted she wouldn’t pick Edward Cullen today, a...

When Fear, Fury & Feathers Collide: Cinema, Superheroes, and a Confessional Album

Open with tension—the kind that threads through a scream, a reveal, and...

Leave a comment