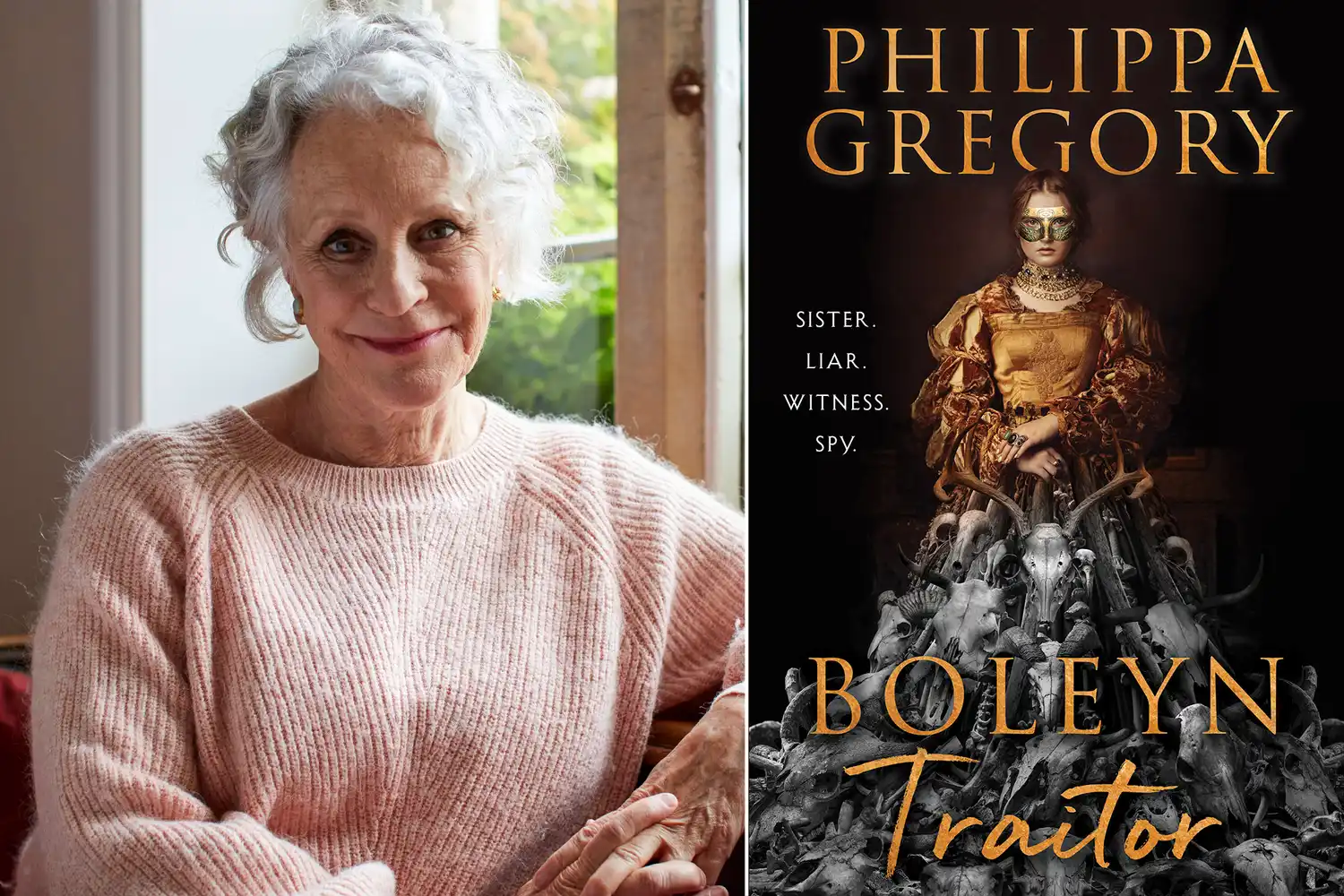

The Boleyn Curse: Philippa Gregory’s Latest Novel Dares to Rewrite the Royal Narrative

What if Anne Boleyn wasn't the seductress we’ve been sold, but the scapegoat of a nation addicted to spectacle? Philippa Gregory returns with a revisionist firebomb.

Anne Boleyn was not the beginning—she was the reckoning.

That’s the first whisper you hear in Philippa Gregory’s The Boleyn Traitor, her newest offering in a lineage of royal fiction that has long delighted, divided, and—quietly—radicalized. But this time, Gregory doesn’t just toy with power dynamics. She detonates them. The story isn’t about seduction or political ambition; it’s about erasure, gender, and the vicious elegance of survival beneath a crown that never fit any woman well.

In the first lines of the exclusive excerpt, we’re introduced to the architecture of betrayal: hushed courtrooms, hungry courtiers, and the steady beat of history’s favorite execution. And yet, beneath the brocade and blood is a portrait not of a queen but of a pawn, a girl twisted into myth by men with quills sharper than any axe. Gregory doesn’t just humanize Anne Boleyn—she repositions her as history’s tragic influencer, a woman punished for the very charisma that made her indispensable.

A Kingdom Addicted to Women’s Ruin

We tend to forget how obsessed the English monarchy has always been with performance. Every marriage, every coronation, every execution—staged like opera. Anne Boleyn wasn’t the villain. She was the finale. Gregory leans into this idea with poetic ruthlessness, weaving a plot where legacy is less about lineage and more about who survives the retelling. The new novel centers Catherine Carey, Anne’s niece, a figure usually lost in the footnotes. By making her the narrator, Gregory flips the entire Tudor lens: what if the side character remembers more than the queen ever could?

One line in the book lingers like perfume after a locked room has cleared:

“They said Anne bewitched him. No one asked what it took to survive being beloved by a king.”

That’s Gregory’s true rebellion—rewriting the assumptions baked into our schoolbooks and Netflix algorithms. For decades, Anne Boleyn has been filtered through the male gaze, her intelligence eroticized, her ambition punished. The Boleyn Traitor suggests something more insidious: that Anne’s real crime was becoming more compelling than the men around her.

Truth, Dressed for Court

Gregory’s work has always thrived in the shadows of power, but this novel feels different—darker, more dangerous. It doesn’t ask for our sympathy; it demands our discomfort. Catherine’s recollections make us complicit in the retelling. We know how it ends—Tower Hill, a French sword, and a prayer whispered through clenched teeth—but Gregory wants us to flinch anyway. Because maybe we were never taught the story right to begin with.

It’s a clever thing to do, releasing a book like this in an era of reexamination. Post-#MeToo, post-truth, post-royal-wedding, we’ve grown tired of sanitized heroines and clean-cut villains. We want mess. We want conflict. We want the politics of the past to make us question our present. Gregory gives us that in spades—and pearls, and poison, and papal excommunications.

So where does that leave Anne Boleyn? A cautionary tale? A feminist icon? A marketing ploy? Or perhaps—more unsettling still—something else entirely: a woman whose story was never hers to tell.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s the real royal scandal.

Explore more

When “107 Days” Meets Outcry: Harris’s Book Tour Interrupted

The microphone crackled to life, and before Harris could finish her opening...

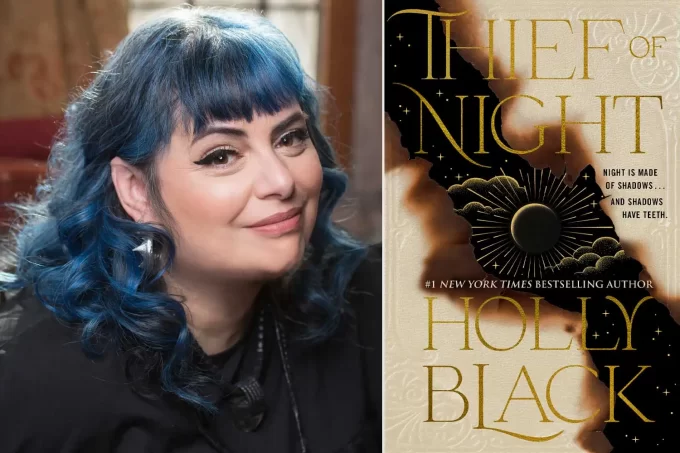

Whispers in the Shadows: Why Holly Black’s Sequel Is a Dark Invitation We Can’t Ignore

The night isn’t just dark—it’s ravenous, greedy, and it’s coming for you....

Why Stephenie Meyer’s Regret About Edward Changes Everything You Thought You Knew

The moment Stephenie Meyer admitted she wouldn’t pick Edward Cullen today, a...

When Fear, Fury & Feathers Collide: Cinema, Superheroes, and a Confessional Album

Open with tension—the kind that threads through a scream, a reveal, and...

Leave a comment