The Long Walk Is Here—But Are We Ready to Watch Boys Die for Applause?

Stephen King’s most disturbing story has finally made it to the screen, but its arrival in our current cultural moment is as eerie as the story itself. What does it mean to cheer for suffering dressed as spectacle?

They don’t run. They walk. One foot in front of the other. No resting, no stopping, no turning back. And when they falter—because they always do—there is a bullet waiting. The quiet horror of The Long Walk is not in the blood, but in the rules. Rules so absurd, so cruel, they could only come from a society that has forgotten the value of breath.

Stephen King wrote the book in his early twenties, under the pen name Richard Bachman—when the idea of youth as a disposable asset felt more speculative than real. Now, over 40 years later, The Long Walk emerges not just as a film, but as a mirror. One we may not want to look into. What happens when dystopia no longer feels like fiction, but an echo of the systems we’ve normalized?

Pretty Corpses in the American Sunlight

It is not lost on anyone that the protagonists are teenage boys. Young, athletic, patriotic in that confused, aching way boys are when they’ve only been taught to perform masculinity, never question it. They walk because it’s an honor. They walk because everyone’s watching. They walk because the alternative is worse: irrelevance.

In this story, survival is entertainment. There are cheers from the sidelines. Smiles on the faces of people who do not see death, but drama. The horror of The Long Walk isn’t in what it invents—it’s in what it recognizes. A culture that feeds on its youth with the hunger of a starved beast, dressed in the glitter of reality television and the rhetoric of “earning your place.”

One of the boys, exhausted and terrified, whispers, “You keep walking because you can’t stop. You forget why.” And maybe that’s what’s most terrifying: not the bullets, but the blind momentum.

Dystopia Is Having a Moment, and It’s Boring

We are drowning in dystopia—and we’re numb. It’s not just that we’ve seen this before. It’s that we’ve started to like it. The Hunger Games, Battle Royale, Squid Game, and now The Long Walk. These are not warnings anymore. They are franchises. There is something disturbingly chic about watching children die in cinematic slow motion, their bodies beautiful, their pain aesthetic.

But The Long Walk was never meant to be beautiful. It was meant to make you uncomfortable. And if this new adaptation polishes its horror too finely, it risks becoming exactly what King was warning us about: a parade of sanitized agony for an audience trained to consume cruelty as catharsis.

So we must ask: who is this film really for? And why does it arrive now, in an age where teenage burnout, digital voyeurism, and moral fatigue are the air we breathe?

Maybe The Long Walk isn’t about the boys. Maybe it’s about us. The spectators. The ones who clap when a body falls, then refresh the feed for more.

And if the world keeps walking—feet blistered, heads down, rules tightening like a noose—who gets the final bullet when no one can remember where they were walking to in the first place?

Explore more

Meet the Actors Behind the Netflix Series – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Courtesy of Netflix The Straw Hat Pirates are setting sail...

Release Date, Plot, Cast & More Updates – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: The Hollywood Reporter via Getty Disney is officially bringing Tangled...

Who Will Win 2026 Best Actor? – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images Timothée Chalamet and Michael B. Jordan...

What Happened Between Them? – Hollywood Life

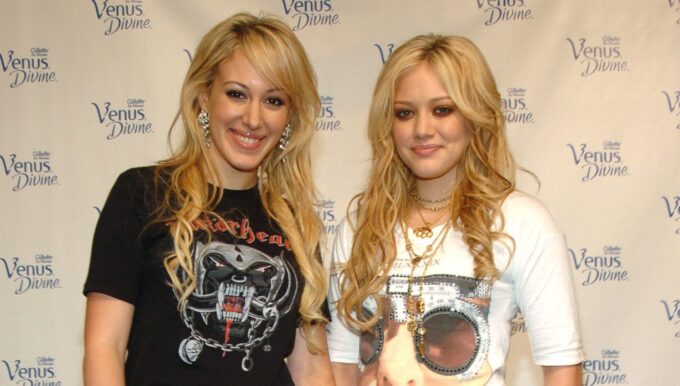

View gallery Image Credit: WireImage Hilary Duff and Haylie Duff were once...

Leave a comment