Pedro Pascal’s Hair Wasn’t the Real Villain in Wonder Woman 1984

In a candid admission, Pedro Pascal called his Wonder Woman 1984 look “appalling”—but what if the real horror wasn’t in the mirror, but in the system that shaped it?

It’s not often a Hollywood leading man calls himself “appalled” by his own on-screen transformation, but Pedro Pascal, ever disarming and exacting, does just that. With a mixture of deadpan honesty and ironic self-awareness, he recently confessed that his Wonder Woman 1984 look—an oily, power-hungry tycoon drenched in late-’80s bombast—shocked even him. But perhaps the hair was never the problem. Perhaps the unsettling part was how easily he slipped into the mask we all recognized too well.

Maxwell Lord wasn’t just a villain—he was a mirror. And not the flattering kind. The glint in his eye wasn’t only Pascal’s performance; it was a commentary on the charisma of corruption. The blow-dried bravado, the synthetically tanned skin, the hollow promises—those weren’t design choices, they were cultural artifacts. It’s no wonder Pascal recoiled. Who wouldn’t, staring into that kind of grotesque familiarity?

When Nostalgia Becomes the Villain

Hollywood loves the 1980s, but it often forgets the shadows beneath the shoulder pads. Pascal’s discomfort reveals more than just aesthetic distaste—it surfaces something few actors dare to admit: transformation can be invasive. “I saw the look, and I was appalled,” he said, laughing. But was the laughter shielding something more disturbing? An actor’s body and face are instruments—but who tunes them, and to what end?

That decade’s slickness has returned to fashion, television, even politics—but Wonder Woman 1984 weaponized it. Maxwell Lord was excess personified. He didn’t simply sell lies; he sold the idea that desire was truth. And when Pascal looked at himself in full costume, maybe he saw what audiences were meant to: that this character wasn’t a parody. He was a prophecy.

The Beauty in Discomfort

It’s a rare kind of honesty in an industry addicted to polish. To say “I hated how I looked” isn’t a vanity complaint—it’s a protest. One wonders how often actors wear personas that repel them, and what toll that takes. Pascal’s revulsion is fascinating not because it was dramatic, but because it was real. And because it came from a place of artistic clarity: he understood the role so well, it made his skin crawl.

In a world where appearance is currency, disliking the mask you’re handed is practically revolutionary. Maxwell Lord wasn’t just gaudy; he was dangerous. Not for his wishes, but because of how eerily familiar he felt. The look? It wasn’t appalling because it was unattractive—it was appalling because it was believable.

So the question isn’t why Pedro Pascal hated his look. It’s whether we should’ve hated it more. If discomfort is the price of truth, maybe more roles should make us wince.

And maybe the next time Hollywood conjures a villain from the past, we won’t just ask what he’s wearing—we’ll ask what it says about us.

Explore more

Where Is Liam Conejo Ramos Now? Updates on 5-Year-Old’s ICE Detainment – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images Liam Conejo Ramos came home from preschool while...

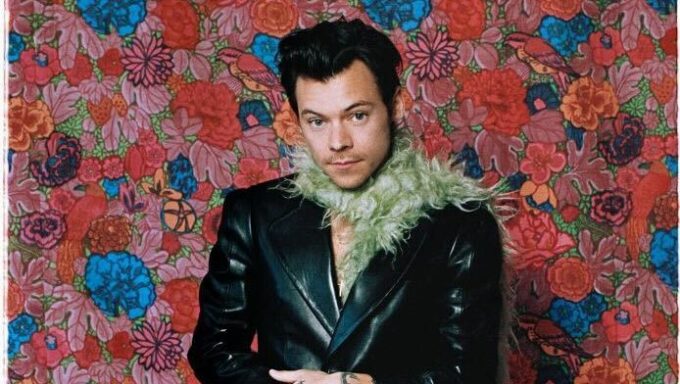

Who Is Harry Styles’ ‘Aperture’ About? Breakdown of the Lyrics – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images We’ve doing doing all this late...

When Are the Oscars 2026? Date of the Academy Awards – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images The Oscars are officially on the...

Ticket Prices & Presale Details – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Dave J. Hogan/Getty Images Harry Styles is embarking...

Leave a comment