The Floating Worlds of Ghibli: Why We’ll Never Agree on What’s “Best”

Studio Ghibli films aren’t meant to be ranked—they’re meant to be remembered. And yet, we keep trying to pin down the ungraspable magic of a moving castle, a soot sprite, or a quiet train ride through nowhere.

The arguments usually begin with “Spirited Away,” which is telling. It’s not that the film doesn’t deserve the pedestal—it’s that its pedestal has been polished so smooth by praise, there’s no longer room to hold on. People mention “My Neighbor Totoro” with a smile, “Princess Mononoke” with a furrowed brow, and “Howl’s Moving Castle” like a dream they’re not sure they actually had. These are not just movies—they are memories. And you cannot rank a memory. You can only carry it.

Still, the lists keep coming. EW’s recent ranking of all Studio Ghibli films has reawakened that familiar ache: how do you define greatness in a universe that defies structure? What logic places Nausicaä below Kiki? What rubric dares to separate Grave of the Fireflies from Ponyo except the cold arithmetic of cultural lists? The moment we try to pin Ghibli down, it shape-shifts. It always has.

The Wild Grace of the Unclassifiable

Studio Ghibli films aren’t about arcs, they’re about atmospheres. In Hollywood, characters must change. In Ghibli, they must feel. The emotional grammar is different. Consider The Wind Rises—half biography, half elegy, and entirely misunderstood outside Japan. Or Only Yesterday, a film so quiet, so gentle, it feels like leafing through someone else’s diary. What do you do with a movie where the plot is less important than the way sunlight filters through a memory?

“Miyazaki doesn’t make films,” one critic once mused, “he makes windows.” That line has haunted me. Because what we’re peering through in these films isn’t narrative—it’s soul. There’s a reason Studio Ghibli never felt the need for sequels or cinematic universes. They understood that once you visit a spirit world, you don’t return for franchise potential. You return because something inside you has been altered.

Not Meant to Be Ranked, Only Revisited

There’s also the quiet resistance in these stories. In Mononoke, nature doesn’t forgive. In Totoro, nothing is explained. In Ponyo, love is childish and that’s the point. These films refuse the frameworks that critics love: tension, climax, resolution. They are stories that wander, that pause, that observe a child watching dust settle in a beam of light. They are, in that sense, radically subversive.

And maybe that’s why we keep trying to rank them—because we don’t know how else to process the way they linger. These lists are less about declaring winners and more about decoding our own attachments. Are we soot sprite people or Cat Bus people? Do we live in the world of Laputa, or long for the simplicity of Kiki’s Delivery Service? Our rankings reveal less about the films, and more about ourselves.

So when EW or any outlet dares to line them up like racehorses, it’s a provocation. A beautiful, maddening, necessary provocation. Not because Ghibli films should be compared—but because they resist comparison so exquisitely.

Explore more

Pianist Omar Harfouch Brings Celebrated Figures Together for a Night of Cultural Exchange – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Omar Harfouch On February 20, 2026, pianist and cultural figure...

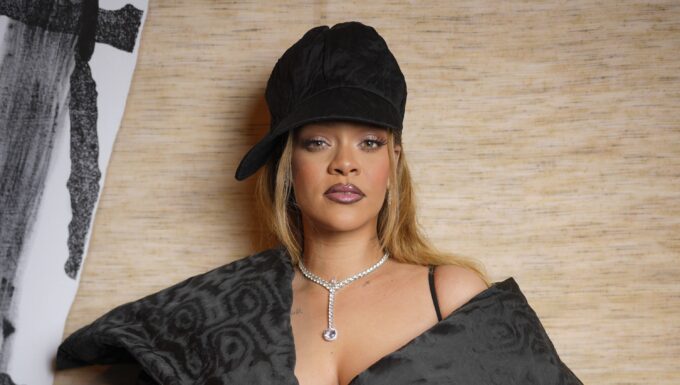

How Much Money Does She Have Now? – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images Rihanna may be known as one...

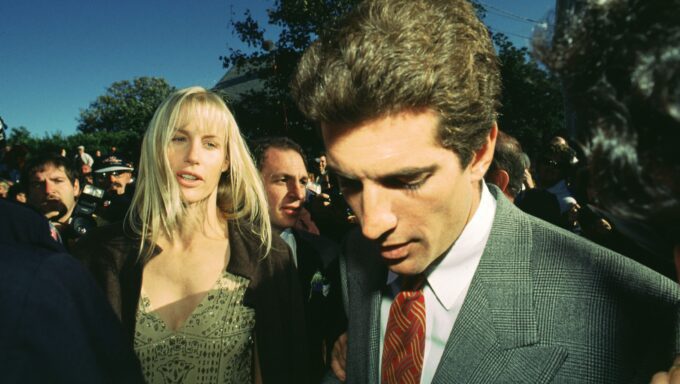

Stars Who Slammed ‘Love Story: JFK Jr. & Carolyn Bessette’: Statements – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images FX’s Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and...

Find Out Release Date, Cast, Plot Details & More – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Courtesy of Amazon Freevee After its breakout first season, Jury...

Leave a comment