Camille’s Exit: A Farewell Dressed in Rebellion

Camille Razat leaves Emily in Paris, but this is no gentle adieu—it’s a chic departure with the sharp edges of reinvention. The question now isn’t where she’s going, but who she’s becoming.

She walked away in heels, of course. Not the clicky, cliché kind—Camille Razat’s stride felt quieter than that. More deliberate. A departure not just from a show, but from an idea of herself that the world had dressed her in. The kind of role that fits like couture but slowly starts to feel like a costume.

When Emily in Paris introduced Camille—the effortlessly Parisian foil to Emily’s American effervescence—audiences were hypnotized. Here was a woman sculpted in bone and brevity, the embodiment of cool indifference. But the Camille who’s stepping off that glossy Netflix carousel isn’t disappearing into smoke. She’s entering her own frame for the first time. And she’s not smiling politely anymore.

What Is a Muse Without the Mirror?

There’s something both dangerous and divine about an actress who leaves at the height of visibility. It defies the rules—especially the unspoken ones Hollywood writes in invisible ink. “I wanted to explore the parts of me that weren’t being seen,” Camille reportedly said. Not as a throwaway line, but like someone peeling back silk to reveal something rawer underneath.

She has been too easily cast as the accessory to someone else’s arc—too many fashion spreads, too many stills where she’s seen, not heard. But Razat’s silence always held a shape. Her performance was less about dialogue and more about what lingered in the spaces between. Her eyes did the talking. Now, the rest of her gets to speak.

A Beautiful Exit Is Always a Beginning

The fashion world has long adored Camille—because she wears ennui like it’s embroidered. But acting is less forgiving. It demands not only transformation, but exposure. Her next project, whatever it is, won’t have the pastel crutches of Paris or the safety net of ensemble casts. It will demand a nakedness—emotional, aesthetic, maybe even literal.

Still, this is where the intrigue thickens: is Camille building a career, or dismantling one version of herself to construct another? We’ve seen this before, haven’t we? The It Girl who pivots into danger, the ingénue who finally gets tired of being gentle. But with Camille, it’s harder to read. She’s all angles and half-answers, the kind of woman you remember differently each time.

So she walks. Past the cafés, out of the screen, and into something else. And if she’s burning a bridge behind her, she’s doing it in velvet gloves.

What does a woman become when she stops being everyone’s aesthetic fantasy?

Explore more

When Mercy Meets Tragedy: The Widow Who Forgave Her Husband’s Killer

The air thickens when forgiveness enters a room meant for grief. Imagine...

When Fear Became a Lifeline: Pete Davidson’s Reckoning in Rehab

There’s a silence that follows a mother’s voice when she confesses her...

Pete Davidson’s mom told him in rehab worst fear was learning he died

Pete Davidson is opening up about the heartbreaking moment he had with...

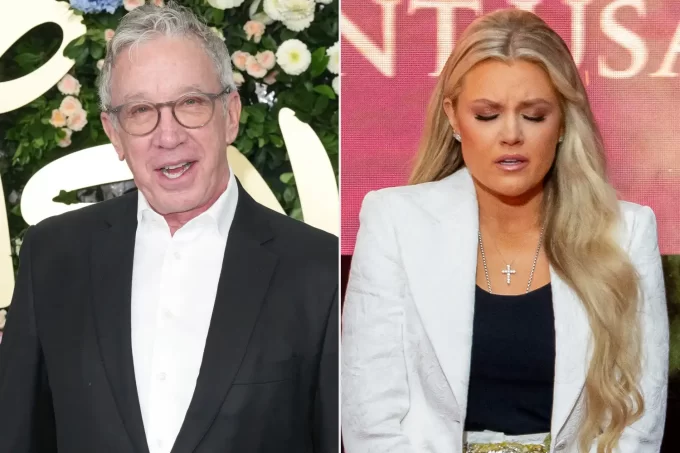

Katie Couric’s Unexpected Spin on Sydney Sweeney’s American Eagle Ad: What’s Really Being Said?

Katie Couric stepping into a scene dominated by Gen Z glamour feels...

Leave a comment