The Kebab Van That Hijacked a Bestseller

A love story set in Oxford. A real-life kebab van. A copyright fight no one saw coming. What happens when fiction steps too close to fact—and why this strange dispute has everyone quietly panicking.

A girl meets a boy under the drunken hum of an Oxford streetlight. There’s romance, academia, loss—and a kebab van. Not just a kebab van, but the kebab van. Stainless steel, parked outside a college gate, slinging greasy chips and garlic sauce to hungover students. Except this van isn’t fiction. It’s real. And it wants royalties.

When My Oxford Year hit shelves in 2018, Jo Piazza’s novel was billed as a fresh new entry in the “rom-dram” canon. Reese Witherspoon’s production company even eyed it for adaptation. But in a plot twist that could have come from the third act of its own movie, a dispute erupted between the novel’s creators and the real-life operators of the food truck it so vividly described. The van—an actual Oxford institution affectionately known to locals—has now become an unexpected protagonist in a copyright storm no one anticipated.

When Fiction Forgets It’s Being Watched

It’s easy to imagine this as satire: a kebab van suing a publisher. But the legal foundation isn’t a punchline. Embedded deep within the novel are detailed references to the real van’s name, location, menu, and cultural lore—details that, according to the owners, were used without permission. “You can’t just borrow someone’s life and wrap it in fiction,” one of them told Entertainment Weekly, “especially if you’re profiting from the brand they built.”

The implications are chilling. Writers have always leaned on real-life fragments—cafés, trains, bars, cities—as scaffolding for fiction. But at what point does a setting become property? Can a kebab van be copyrighted in the same way as a song lyric or an iconic logo? This is no longer a question for writers’ rooms. It’s one for courtrooms.

And the stakes are rising. With streamers devouring book options like tapas, there’s a new hunger for authenticity. But authenticity, it turns out, may come with a legal invoice.

Romance, Rights, and the Price of Atmosphere

There’s also a deeper tension at play: the exploitation of local color for global profit. When American authors—or producers, or publishers—romanticize British institutions like Oxford, it often comes cloaked in charm. Quaint vans. Cobbled streets. Haunting towers. But whose story is it, really? The van, in this case, wasn’t just atmospheric garnish. It was a character. A business. A livelihood.

The irony, of course, is cinematic. A novel about idealism, youth, and loss now draped in legalese. Yet the broader industry is watching with a nervous eye. If a kebab van can claim infringement, what’s next? A neighbor’s cat? A dive bar in Berlin? A psychic in New Orleans who once gave a reading that became a plot point?

What this case reveals isn’t just a grey area—it’s the soft, foggy terrain between homage and theft. Writers mine the world for stories, yes. But the world is beginning to mine back.

The kebab van is still parked where it always was, serving late-night pilgrims and weary undergrads. But now, it’s more than a stop for food. It’s a site of cultural reckoning. A reminder that even the smallest details, when lifted into story, carry weight.

Maybe the real question isn’t whether fiction should borrow from life. It’s whether life is finally ready to bill fiction for the favor.

Explore more

Pianist Omar Harfouch Brings Celebrated Figures Together for a Night of Cultural Exchange – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Omar Harfouch On February 20, 2026, pianist and cultural figure...

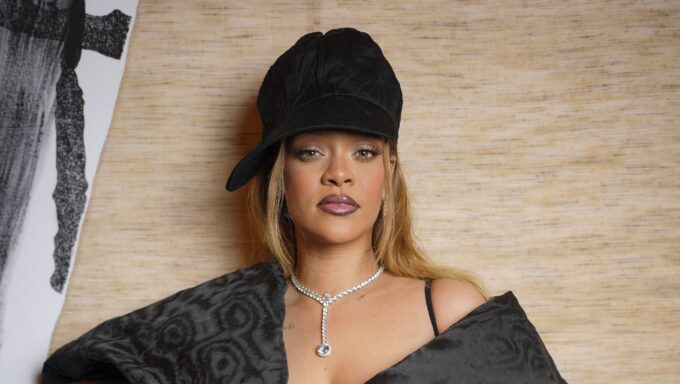

Who Is Ivana Lisette Ortiz? About the Rihanna Home Shooting Suspect – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images The suspect in the March 8,...

What Channel Are the Academy Awards On? – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images The 2026 Academy Awards will bring...

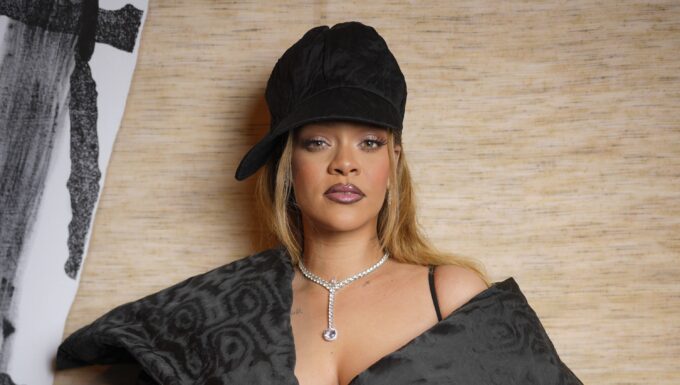

How Much Money Does She Have Now? – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images Rihanna may be known as one...

Leave a comment