Why Classic Movies on Netflix Feel More Subversive Than Ever

They weren’t made for streaming, and that’s precisely why they haunt it. Netflix’s classic films aren’t just cinematic history—they’re a quiet rebellion against what cinema has become.

The screen glitches for a split second—a hiccup of buffering—and then: Audrey Hepburn steps out of a cab, her eyes as sharp as the tailoring of her black Givenchy dress. Breakfast at Tiffany’s, reborn in pixels. It’s not the image that jolts you. It’s the realization that somewhere between algorithm-driven rom-coms and multiverse fatigue, Netflix has quietly become a museum of ghosts.

And yet, this museum doesn’t advertise itself. There’s no fanfare when Chinatown slips onto the platform. No carousel banner for All the President’s Men. These films appear almost accidentally, like misfiled relics—elegant, unnerving, whispering secrets about storytelling from a time before streaming swallowed context. They exist in quiet defiance of autoplay culture, inviting a slower, more dangerous kind of watching.

Velvet Rebellion on a Digital Shelf

There’s a kind of seduction in seeing The Conversation nestled beside a made-for-streaming teen drama. It’s less nostalgia and more a clash of tempos. These older films don’t beg you to like them. They unfold. They wait. They dare you to have patience. And somehow, that patience feels radical now.

Streaming platforms weren’t built for the long take, the slow burn, or the unresolved ending. But the classics—those real, rusted-bolted classics—thrive on all three. “You have to meet them on their terms,” a director once told me over dinner in Venice, “They weren’t made to compete with your notifications.” Indeed, when 12 Angry Men plays on a screen where you can also swipe to TikTok, it becomes more than a legal drama—it becomes a social experiment in attention.

Elegy in the Algorithm

The presence of these films feels less like programming and more like protest. There’s no data suggesting millions are clamoring to rewatch The Third Man. And yet, there it is. Like Orson Welles’ shadow in the sewer—uninvited, unforgettable. The classics on Netflix are not curated for trend—they are haunted curation, accidental time machines left running in the basement of the content factory.

And in that haunt lies their danger. These films were made in eras where studio interference came in the form of a cigarette-smoking mogul, not a page of viewership metrics. They were flawed, yes, but they were alive. They carry the scent of risk, and the stubborn belief that cinema, like literature, is allowed to be difficult.

What makes them suddenly feel urgent—almost punk—isn’t just that they’re good. It’s that they are not trying to be liked. In an age of soft edges, that jagged refusal is a kind of poetry.

Watch The Apartment on Netflix and you may find yourself questioning your own emotional bandwidth. Not because it’s tragic, but because it assumes you can follow a thought for more than five seconds. Watch Network and feel the sting of 1970s satire that somehow saw the future of media clearer than we see the present. Watch Bonnie and Clyde, and you’re watching violence reclaim style as narrative.

These aren’t just “classics.” They’re cinematic subversion dressed in pressed suits and film grain.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s what keeps them dangerous. Because when an old film survives the storm of streaming sameness, it doesn’t just endure—it resists.

So the next time your cursor hovers over a 1960s title buried beneath three rows of forgettable thrillers, don’t scroll. Click. Let the past remind you that cinema wasn’t always this easy to digest.

And ask yourself: What did we trade for convenience?

Explore more

Pianist Omar Harfouch Brings Celebrated Figures Together for a Night of Cultural Exchange – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Omar Harfouch On February 20, 2026, pianist and cultural figure...

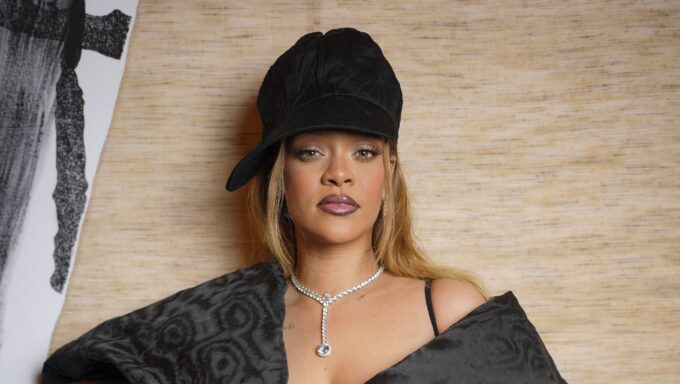

Who Is Ivana Lisette Ortiz? About the Rihanna Home Shooting Suspect – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images The suspect in the March 8,...

How Much Money Does She Have Now? – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images Rihanna may be known as one...

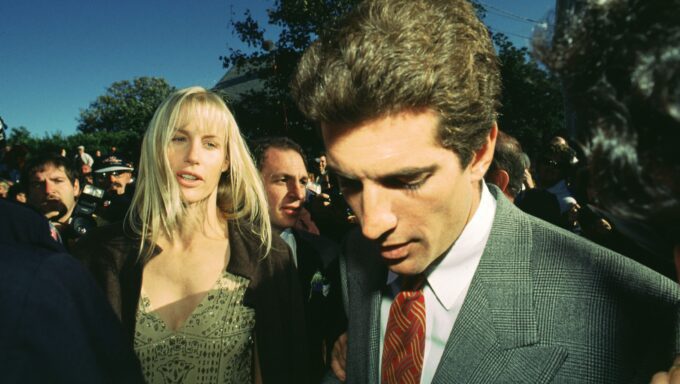

Stars Who Slammed ‘Love Story: JFK Jr. & Carolyn Bessette’: Statements – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images FX’s Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and...

Leave a comment