Why Stephenie Meyer’s Regret About Edward Changes Everything You Thought You Knew

Stephenie Meyer’s surprising admission that she wouldn’t choose Edward Cullen today sends a ripple through the Twilight fandom—and beyond. What does this mean for the iconic vampire’s legacy, and why does it unsettle everything we believed about love, obsession, and storytelling?

The moment Stephenie Meyer admitted she wouldn’t pick Edward Cullen today, a collective shiver passed through the Twilight universe. It was never just about vampires and glittering immortals—it was about an idea of love frozen in amber, eternal and unyielding. Yet here she is, the architect of one of the most iconic romantic figures of the 21st century, casting doubt on her own creation. What if Edward isn’t the timeless fantasy we thought? What if, buried beneath the sparkling veneer, lies something more complicated, more troubling?

Is this confession a simple act of hindsight, or a radical rethinking of a cultural phenomenon? More than a decade after Twilight transformed vampire lore into mainstream obsession, Meyer’s words unravel the neat narrative many of us told ourselves about desire, control, and fantasy.

Glittering Facade, Cracks Beneath

Edward Cullen has long stood as a beacon of brooding perfection—protector, lover, immortal. But Meyer’s hesitation invites a darker, more unsettling interrogation. Was Edward always a symbol of something else—an embodiment of control masked as devotion? When she states she might not choose him today, Meyer forces us to reconsider not only the character but also the culture that embraced him. Could the fandom’s adoration have been a yearning for something far less romantic? Or does this reveal a shift in how we view relationships and power dynamics in fiction?

One can’t ignore the cultural currents: the rise of conversations about consent, emotional complexity, and toxic masculinity now coloring how we read characters like Edward. Meyer’s words echo with the tension of a society questioning old fantasies and seeking newer, messier truths.

The Author’s Shadow: Creator vs. Creation

It’s rare when an author disavows their most famous creation with such candor. Meyer’s remark feels less like regret and more like a challenge thrown to her audience—“What would you choose now?” This challenges readers to interrogate their own attachments. The cult of Edward Cullen wasn’t just about a vampire; it was a mirror reflecting collective longings, fears, and youthful fantasies of control and escape. Meyer’s voice adds a layer of complexity, reminding us that authors are not gods but humans, subject to change, critique, and reflection.

“There’s always a dialogue between author and reader, but sometimes the author shifts the ground beneath the reader’s feet,” a literary critic recently noted. Meyer’s admission does exactly that—turning the familiar into something unsettlingly ambiguous.

What does this mean for the millions who once found solace in Edward’s unwavering devotion? And what does it say about the stories we cherish and the versions of ourselves we project onto fictional characters?

The last word isn’t Meyer’s—it’s ours to wrestle with. And as the twilight fades, we must ask: who do we want to be in the stories we tell next?

Explore more

When “107 Days” Meets Outcry: Harris’s Book Tour Interrupted

The microphone crackled to life, and before Harris could finish her opening...

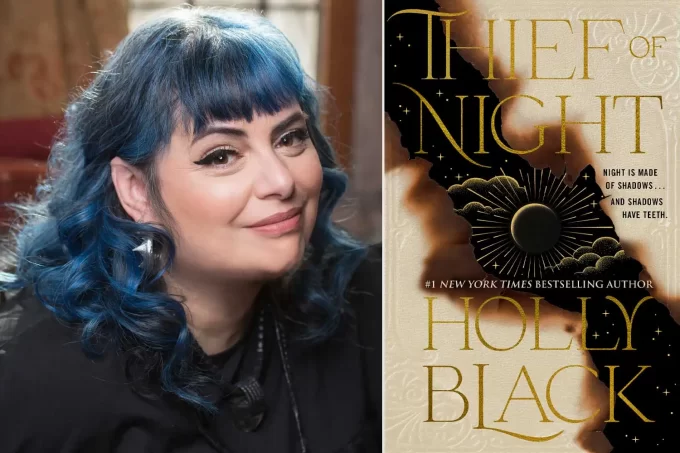

Whispers in the Shadows: Why Holly Black’s Sequel Is a Dark Invitation We Can’t Ignore

The night isn’t just dark—it’s ravenous, greedy, and it’s coming for you....

When Fear, Fury & Feathers Collide: Cinema, Superheroes, and a Confessional Album

Open with tension—the kind that threads through a scream, a reveal, and...

When Vampires Plunge: BRZRKR’s Blood‑Soaked Tide Pulls You In

There’s a heartbeat beneath the brine that doesn’t belong—agueing, alien, demanding. You’re...

Leave a comment