Rib-Rattled: The Hidden Toll Behind Caught Stealing’s Flesh and Fury

Austin Butler traded safety for raw truth—nearly cracked a rib from a headbutt and flew onto a wooden table in his underwear, all for cinematic authenticity that aches with unspoken stakes.

A headbutt lands like a secret betrayal—each rib has a story, and Austin Butler’s nearly fractured one in Caught Stealing is a confession disguised as cinema.

He tells it almost breathlessly: the punches were originally softened, but then Nikita Kukushkin—“like a little ram”—delivers a head strike so visceral it almost cracks Butler’s rib. He didn’t flinch, even as the room tilted on its axis. It’s the kind of moment you don’t rehearse for—you surrender to it. And then there’s the table: a soft foam prop swapped for real wood. Butler, nearly naked, is slammed down again and again. Pain wasn’t a byproduct—it was the price of truth. He had a stunt double, but said, plainly, “For the most part… ’Yeah, let’s go.’ I’ll just deal with the bruises later.”

He’s not just performing; he’s inhabiting bodily risk. Ask yourself—do we even remember actors who play it safe?

Two Acts of Creative Carnage

Quiet violence in plain sight

Butler’s confession isn’t theatrical. It’s quiet: “I get beaten up by these two Russians in this film… this one—Nikita… didn’t want to kick me very hard… I kept telling him, ‘Just kick me harder.’” Then he headbutts me, Butler marvels. And even pain sounds like praise when draped in performance.

Bruises as badges

Foam gave way to wood because Aronofsky wanted authenticity. Butler lay there, exposed—no armor, no buffer. The bruises aren’t makeup—they’re crests of commitment. In every echo of that slam, you feel ambition wrestling with flesh.

We opened with the anatomy of a headbutt and close by: what is courage if not a broken rib told as a trophy? The film may be titled Caught Stealing, but what about the parts stolen from the actor—the safety, the restraint, the easy path? That rib, nearly fractured—will it linger as memory or myth, asking us: how much of an actor remains actor, and when does he become the story?

And as the lights fade, you feel a quiet shift—pain, not performance, may be the truest language of art . . .

Explore more

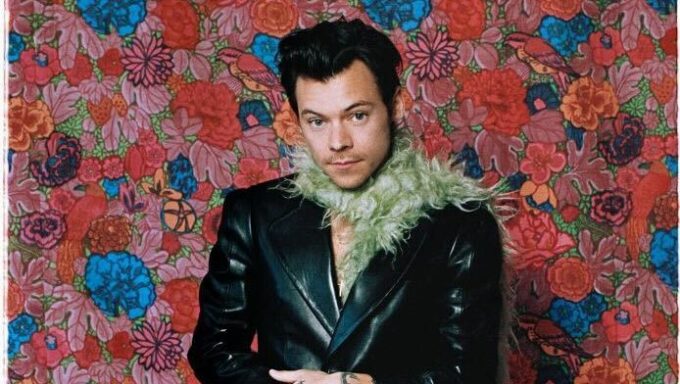

Who Is Harry Styles’ ‘Aperture’ About? Breakdown of the Lyrics – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images We’ve doing doing all this late...

When Are the Oscars 2026? Date of the Academy Awards – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images The Oscars are officially on the...

Ticket Prices & Presale Details – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Dave J. Hogan/Getty Images Harry Styles is embarking...

See Release Date, Cast & Trailer – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: ©2026 Amazon MGM Studios Content Services LLC Masters of the...

Leave a comment