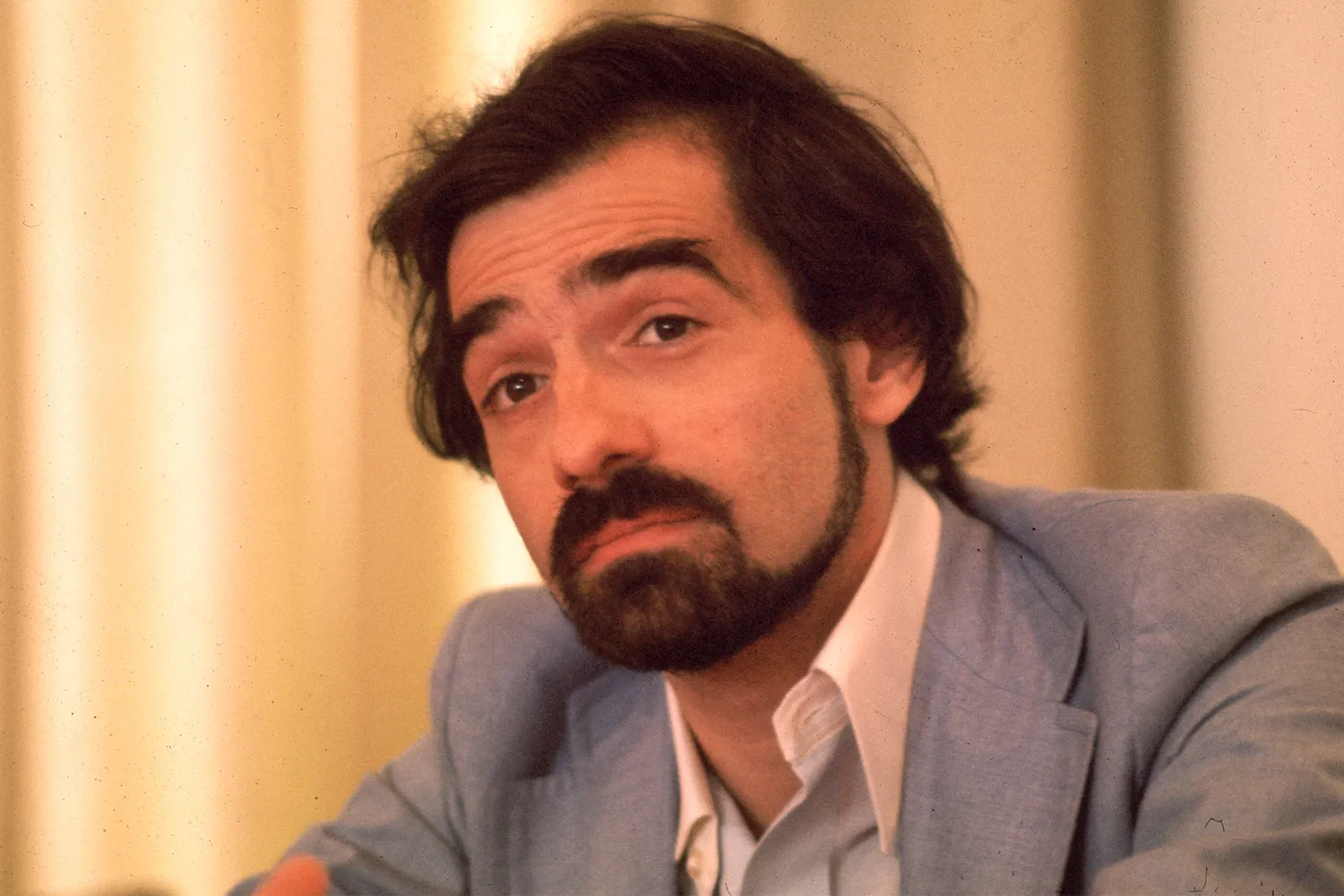

Martin Scorsese’s Last Stand: Can a Gun Save “Taxi Driver”?

Martin Scorsese, the maestro of cinematic grit, contemplates an act so drastic it challenges the very soul of Taxi Driver. What does it mean when a director is ready to rewrite a classic with violence as the savior?

There is a fracture in the polished surface of cinema history. Martin Scorsese, who shaped modern film with Taxi Driver, now flirts with an idea that feels both revolutionary and sacrilegious: wielding a gun to rescue his own work. Not metaphorically, but literally, the director speaks of using real violence to “save” a film that has long been untouchable, iconic, immortalized in celluloid and the cultural imagination. It’s a paradox that demands we ask: when does preservation become destruction? And who gets to decide the fate of a masterpiece?

Taxi Driver has long been a shrine of urban alienation and simmering menace. Yet, in Scorsese’s mind, this very menace might require a new, brutal punctuation. “If I have to use a gun to save Taxi Driver, then maybe I will,” he reportedly said—a statement so loaded it invites endless speculation about the artist’s psyche and the state of cinema itself. Is this a final act of desperation, or a bold declaration that art must evolve by any means necessary? The line between homage and heresy suddenly blurs.

When Legends Need a Reckoning

To propose that a revered film might need “saving” with violence feels like an affront—almost an act of cinematic treason. But Scorsese has never been one to retreat from controversy. This is the man who made antiheroes and moral ambiguity into art forms, whose frames have always been soaked in tension and chaos. His career is defined by pushing limits, not bowing to reverence. Could this readiness to disrupt Taxi Driver be the ultimate statement of artistic control—an admission that no creation is ever truly complete?

Yet, beyond the bravado lurks a deeper cultural anxiety. In an era saturated with remakes, reboots, and endless digital restorations, what does it mean to “save” a film? Is it preservation of image, or spirit? When Hollywood’s machinery reduces classics to commodities, does the artist reclaim power by threatening to upend the very iconography they helped forge? Scorsese’s stance forces us to consider whether the sanctity of cinema is a myth, one that must be shattered for truth to emerge.

The Violence Behind the Lens

Violence, in Taxi Driver, is both a character and a narrative force—uncomfortable, necessary, and haunting. Scorsese’s contemplation of real violence to preserve this legacy strikes a nerve because it collapses fiction and reality. What happens when the tool of destruction becomes a tool of preservation? It forces the audience to confront the paradox of violence in art: is it merely spectacle, or can it be salvation?

“Art is never finished, only abandoned,” Scorsese once said. This readiness to embrace destruction might be the artist’s way of refusing abandonment—an insistence that Taxi Driver is alive, dangerous, and relevant. It’s a challenge to complacency, to the idea that films are relics safe in their glass cases. Instead, Scorsese invites us into a living, breathing conflict between memory and reinvention, between respect and rebellion.

In the end, the question lingers like a shadow in a dimly lit room: if a gun could save Taxi Driver, what else might it destroy? The line between creation and annihilation is thinner than we dare admit. And perhaps, in that fragile space, lies the true essence of cinema—forever poised between reverence and ruin, between silence and a whisper that could shatter everything.

Explore more

Where Is Lawrence Jones on ‘Fox & Friends’? Health Update Amid Hiatus – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images Fans of Lawrence Jones, a Fox & Friends...

Who Is Lexi Minetree? 5 Things to Know About the ‘Elle’ Series Actress – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images for Hello Sunshine Lexi Minetree plays...

Release Date, Cast & Updates on ‘Elle’ – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Courtesy of Prime Video What, like producing a...

Updates on Academy Award Nominations – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Warner Bros. Pictures Awards season kicked off earlier this month,...

Leave a comment