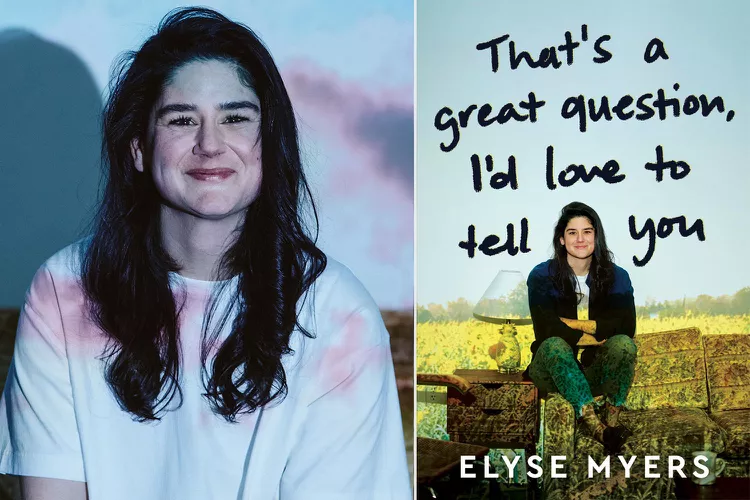

The Comedian Who Refuses to Be the Joke

Elyse Myers made her name by being awkward on the internet—now she’s reclaiming the narrative with a book that reads like a trapdoor into the soul of every overthinker you’ve ever dismissed.

The first thing you notice is the pause. The kind of pause that comes not from shyness, but from calculation—like a woman rehearsing every possible emotional reaction in the milliseconds before she says, “Hi.” That’s the brand of intimacy Elyse Myers has turned into a phenomenon. The glitch, the awkward, the stutter-step of human interaction most of us spend our lives trying to smooth over—she built a kingdom on it.

Now, she’s turned the spotlight inward with That’s a Great Question: I’d Love to Tell You, a memoir that doesn’t seek to tidy up her chaos, but to frame it like a cracked mirror: sharp, revealing, and dangerous if you’re not paying attention. What began as viral storytelling through grainy vertical videos has transformed into a literary excavation of discomfort. And it asks the one thing the internet usually punishes: vulnerability without the safety net of irony.

The Lie of Likability

There’s a price to being “relatable” in the digital age, and Elyse has paid it in full—one self-deprecating punchline at a time. Her stories feel like confessions whispered in the women’s bathroom at a wedding: too personal, too real, too raw to be rehearsed. But read closely, and you’ll find rebellion in the rhythm. Elyse doesn’t just share cringe moments—she weaponizes them.

“I’m not telling you this so you’ll like me,” she writes, “I’m telling you this so I can finally like myself.”

It’s the kind of line that reads like a throwaway until you realize how many women—how many creators, how many people—build entire personalities around being palatable. And what happens when one of them refuses?

Jokes That Bleed

There is a moment in the book—small, but sticky—when she recounts being praised for being “so real” during a mental health spiral. The compliment lands like an insult. She was not being brave; she was being broken. And yet the audience cheered, as if they’d been handed a new kind of content. It’s this uneasy tension that pulses throughout the book: when does storytelling become self-exploitation?

Elyse’s work has always carried this double edge. She’s both the narrator and the narrative, offering a laugh while quietly dissecting the mechanics of why we laugh. Her rise was meteoric, but unpolished. Not a brand, not a scheme—just raw footage of a mind caught mid-loop.

Still, That’s a Great Question isn’t a cautionary tale about fame or a guide to self-acceptance. It’s far messier. It’s about performing your pain before you know how to name it. About asking questions you don’t want answered. And about realizing, perhaps too late, that the internet never forgets—but it rarely understands.

So what do we owe the storytellers who flay themselves for clicks? Can a memoir stitched from digital scars ever offer closure, or does it simply reopen wounds with prettier language?

That’s a great question. Elyse would love to tell you.

Explore more

When “107 Days” Meets Outcry: Harris’s Book Tour Interrupted

The microphone crackled to life, and before Harris could finish her opening...

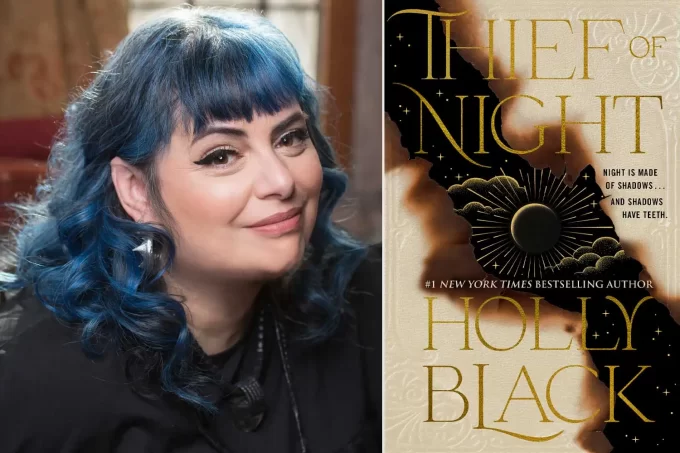

Whispers in the Shadows: Why Holly Black’s Sequel Is a Dark Invitation We Can’t Ignore

The night isn’t just dark—it’s ravenous, greedy, and it’s coming for you....

Why Stephenie Meyer’s Regret About Edward Changes Everything You Thought You Knew

The moment Stephenie Meyer admitted she wouldn’t pick Edward Cullen today, a...

When Fear, Fury & Feathers Collide: Cinema, Superheroes, and a Confessional Album

Open with tension—the kind that threads through a scream, a reveal, and...

Leave a comment