Shelf Lives and Warning Signs

Dystopian books used to whisper about a future we feared. Now they read like diaries we forgot we wrote.

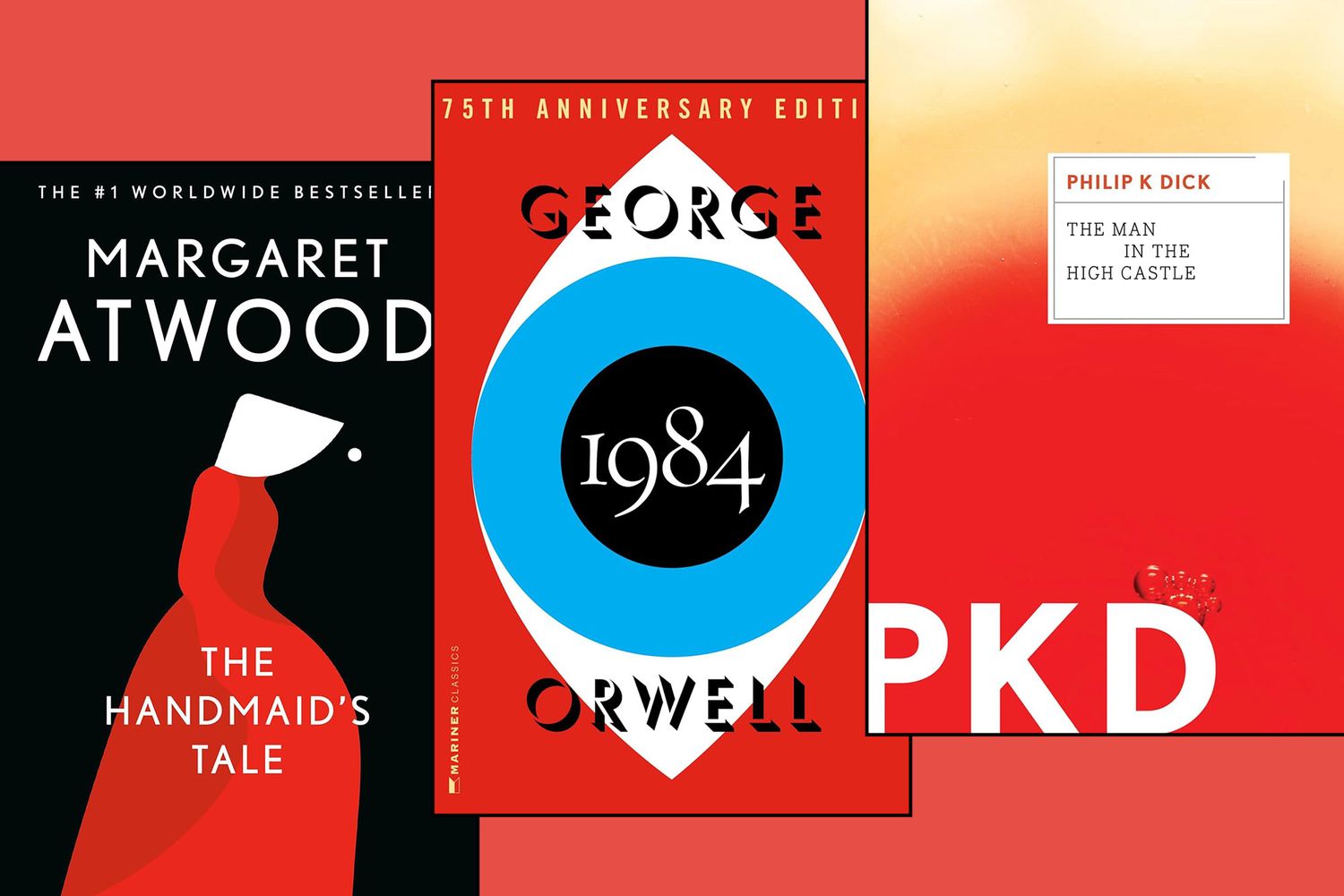

Vintage; Mariner Books Classics (2)

The air feels thinner when you re-read 1984 under fluorescent lights. Not because of its prose, but because of how closely it resembles your last headline scroll. The telescreens, the doublethink, the erasure of memory—it’s all there, now lit by ring lights and wrapped in algorithms. These novels we once dismissed as cautionary—dystopian fiction, we called it—now feel like the only genre willing to tell the truth.

A recent ranking of The 25 Best Dystopian Books of All Time doesn’t read like a celebration. It reads like a lost instruction manual. A sequence of literary flares fired across decades, all ignored. Orwell, Atwood, Huxley, Butler—they didn’t just predict. They knew. They observed how power morphs, how hope dilutes, how control dresses itself up in progress. And yet we keep treating these books as imagination, when they may be the most non-fictional things we own.

Novels That Knew Too Much

There’s a strange cruelty in how we package dystopia for mass consumption. Glossy covers. BookTok recommendations. “Perfect for fans of The Hunger Games,” the blurbs say, as if a story about surveillance and starvation should be accessorized with latte art. The dark joke is on us: we turned prophecy into a mood board.

But these books were never written for comfort. They were screams in narrative form. As Margaret Atwood once said of The Handmaid’s Tale, “Nothing in the book hasn’t already happened at some point in history.” And yet we continue to read it like speculative fiction instead of forensic evidence. That’s not literary reverence—it’s cultural denial.

Our hunger for dystopia has outlasted our patience with reality. We devour books about the breakdown of democracy, the commodification of bodies, the automation of morality—and then refresh our feeds. Perhaps fiction has become the only safe place to feel what we cannot say out loud.

Is Dystopia a Warning, or a Mirror?

What we don’t discuss enough is how dystopian fiction holds a mirror not just to governments, but to readers. To our complicity, our desensitization, our passivity. These books ask: what would you do? And then reveal, slowly and with elegance, that you’ve already done it—by saying nothing.

Newer voices in the genre have taken up this mantle with sharper, even angrier edges. Writers like Ling Ma, M.T. Anderson, and Omar El Akkad don’t use dystopia as prediction—they use it as a form of journalism. Their worlds are not far-off horrors. They are half a breath away. The office that never closes. The refugee with no nation. The child taught to code obedience before language. It is present, just pixelated.

But if fiction is where we hide our truth, what happens when even stories stop giving us the benefit of the doubt?

Maybe the genre has grown tired of waiting for us to listen. Maybe it has begun to archive us the way we archived it—page by page, story by story, proof of how earnestly we ignored every warning sign. And maybe, in the near future, someone will read these books and call them history.

Explore more

When “107 Days” Meets Outcry: Harris’s Book Tour Interrupted

The microphone crackled to life, and before Harris could finish her opening...

Whispers in the Shadows: Why Holly Black’s Sequel Is a Dark Invitation We Can’t Ignore

The night isn’t just dark—it’s ravenous, greedy, and it’s coming for you....

Why Stephenie Meyer’s Regret About Edward Changes Everything You Thought You Knew

The moment Stephenie Meyer admitted she wouldn’t pick Edward Cullen today, a...

When Fear, Fury & Feathers Collide: Cinema, Superheroes, and a Confessional Album

Open with tension—the kind that threads through a scream, a reveal, and...

Leave a comment