Sci‑Fi’s Ghosts and Gods: Why the Best Films Define Our Future

From 2001 to Blade Runner 2049, sci‑fi’s greatest films don't just dazzle—they probe our myths, morals, and meaning. What if the real frontier isn't distant galaxies, but the truths those stories reflect back at us?

A sleek monolith drifts through cosmic void, then a man-ape hurls a bone skyward—cinema’s most daring relationship begins with a primal act. From that silent geometry in 2001: A Space Odyssey, sci‑fi declared itself a religion of ideas. It doesn’t ask us if we believe—it asks who we are.

These films don’t unfold plots—they excavate souls. Blade Runner 2049 doesn’t just show us a dystopia—it challenges the morality of memory itself. The Matrix doesn’t entertain simulations—it interrogates the nature of consciousness. And Looper confronts the fragility of choice when your own future stands before you. They don’t whisper at the edges of our minds—they echo in the core.

When Ideas Become Icons

If 2001 redefined the cosmic unknown, Alien weaponized it—biology as horror. Critics called it a haunted house in space, but decades later, even Roger Ebert agreed it was “a great original” fusion of visceral fear and sci‑fi scope. These films turned abstraction into iconography—engines of cultural power as influential as any blockbuster franchise.

Meanwhile, Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 and Nolan’s Interstellar expand this iconography into moral universes, where aesthetics and ethics collide. Visuals no longer serve spectacle—they frame questions: What is empathy when empathy is engineered? What is love when love is data?

Science or Soul?

Reddit cinephiles debate the terms—hard sci‑fi requiring scientific rigor, or soft sci‑fi using tech as metaphor. But the distinction blurs when the message transcends both. Solaris probes the psyche, Back to the Future redefines nostalgia, and The Fifth Element clashes camp with cosmic couture. Each demands memory, meaning, moral weight.

The question becomes less “Is this plausible?” and more “Does this transform us?” Sci‑fi’s true achievement isn’t world‑building—it’s world‑unraveling: exposing cultural myths, ecological hubris, or our own blind spots.

Explore more

Pianist Omar Harfouch Brings Celebrated Figures Together for a Night of Cultural Exchange – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Omar Harfouch On February 20, 2026, pianist and cultural figure...

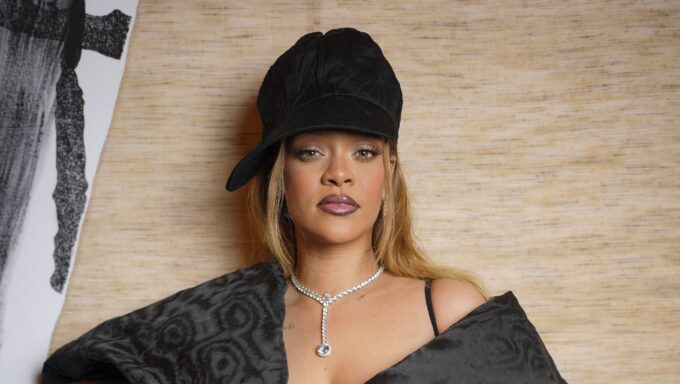

Who Is Ivana Lisette Ortiz? About the Rihanna Home Shooting Suspect – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images The suspect in the March 8,...

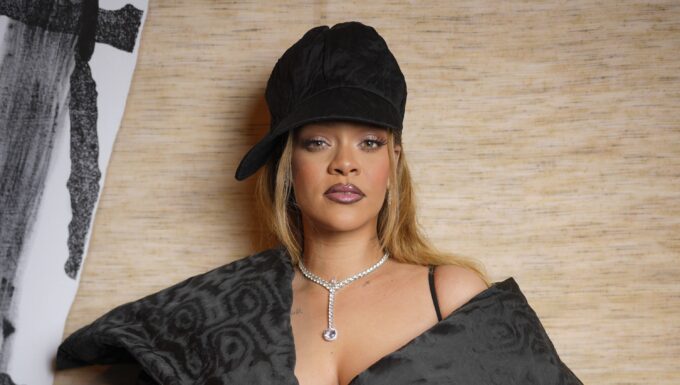

How Much Money Does She Have Now? – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images Rihanna may be known as one...

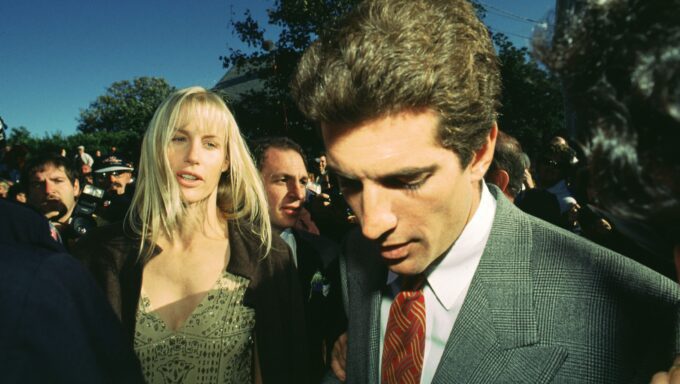

Stars Who Slammed ‘Love Story: JFK Jr. & Carolyn Bessette’: Statements – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images FX’s Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and...

Leave a comment