Tom Hanks in the Wild: The Voice of God or Just a Man with a Mic?

In The Americas, Tom Hanks trades Oscar gold for mossy trails and migratory truths—narrating nature like he’s been waiting his whole life to speak to the trees. But is he channeling David Attenborough, or quietly challenging him?

His voice doesn’t creep. It doesn’t pounce. It ambles—like an old friend showing you the back garden of the planet. But that’s what makes it so uncanny. When Tom Hanks opens The Americas with the solemn hush of “Let us begin where all things once did…,” you’re not entirely sure if he’s narrating a jaguar’s midnight prowl or gently baptizing your subconscious. There is something off-kilter and disarming about America’s Dad whispering over blood moons and predator hunts. As if Forrest Gump grew up, read Thoreau, and started talking to hawks.

We’ve been conditioned to hear the wild from above, through the immortal, British timber of Attenborough. So Hanks, with his everyman cadence and film-worn familiarity, is either breaking a sacred format—or slyly reimagining it. It’s not just that he’s an American telling the story of The Americas. It’s that his voice, so heavily coded with Hollywood lore, now dares to narrate the ancient—bison herds, volcanic births, the low murmur of ice and instinct.

Hollywood in the Undergrowth

It’s easy to forget that Tom Hanks has spent decades studying human nature. Now, he’s turned outward. But can a man whose tone has been fine-tuned for Americana convincingly render the primal? Maybe that’s the twist. He doesn’t try to imitate Attenborough’s reverence. Instead, he imbues the land with something more unsettling: intimacy. A panther doesn’t just leap—it “hovers between breath and blur,” as Hanks describes in one scene, his voice dipping like it’s revealing a secret, not stating a fact.

There’s a theatrical risk here, of course. Nature documentaries demand distance—science dressed in lyricism. But Hanks tugs at that distance, shortening it until the animals become characters, not specimens. “The wind here doesn’t howl,” he murmurs over a storm-flecked rainforest, “it remembers.” Is this poetry, or persona? Or is it both—and that duality the point?

Is This Earth, or Is This Performance?

We live in an age where every narrative must compete. The world isn’t short of wildness—it’s short of attention. So maybe Hanks’ casting isn’t about voice at all, but visibility. Put plainly: who will make middle America watch the Amazon’s breathless decay? Who will make streaming algorithms care about condors and coral reefs? Possibly, only a man who once made us cry over a volleyball.

Yet, there’s a lurking irony: in making nature more human, do we risk making it less real? With Hanks as our gentle guide, do we drift into comfort, even as the planet teeters toward crisis? That might be the gamble of The Americas—to use star power not as spectacle, but as entry point. Whether that’s profound or problematic remains up to the ear of the listener.

By the final episode, as the screen darkens and Hanks offers his parting words to “the places we forget until they disappear,” a strange silence hangs. It’s not closure—it’s echo. Maybe that’s what he’s always been best at. Not telling us what to feel, but making us question why we feel it in the first place. So then, what does it mean when the voice of cinema turns to the voice of Earth? And what will we do when the camera cuts and the animals keep living?

Explore more

When Mercy Meets Tragedy: The Widow Who Forgave Her Husband’s Killer

The air thickens when forgiveness enters a room meant for grief. Imagine...

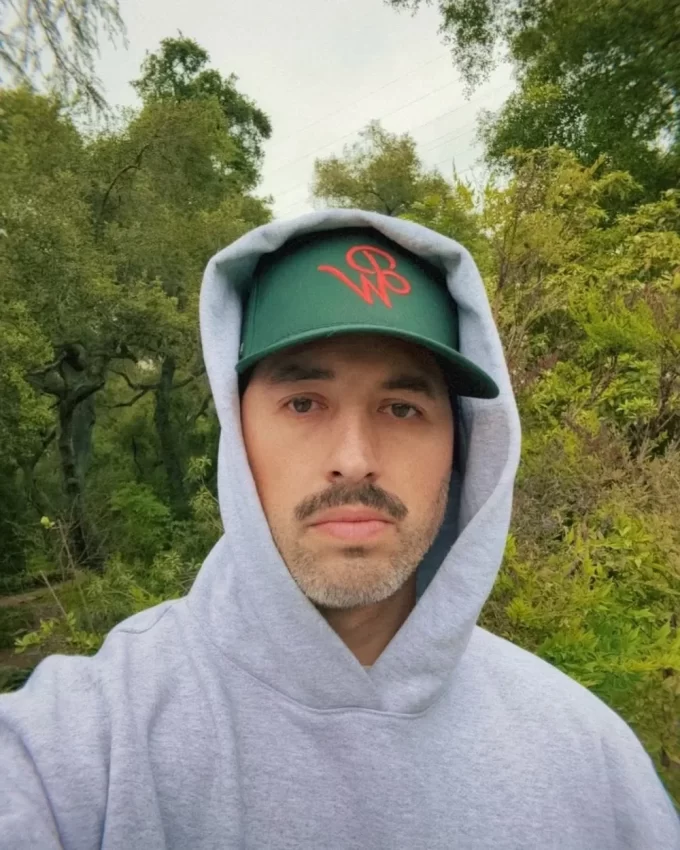

When Fear Became a Lifeline: Pete Davidson’s Reckoning in Rehab

There’s a silence that follows a mother’s voice when she confesses her...

Pete Davidson’s mom told him in rehab worst fear was learning he died

Pete Davidson is opening up about the heartbreaking moment he had with...

Katie Couric’s Unexpected Spin on Sydney Sweeney’s American Eagle Ad: What’s Really Being Said?

Katie Couric stepping into a scene dominated by Gen Z glamour feels...

Leave a comment