The $500 Million Needle: What’s the Trump Play with “Universal” Vaccines?

A half-billion-dollar investment in “universal vaccines” is quietly underway, with Trump’s fingerprints on the blueprint. But what does “universal” really mean—and why now?

They didn’t announce it with a bang—but a whisper. A $500 million bet placed on the most seductive phrase in modern biotech: universal vaccine. The Trump administration, once synonymous with vaccine hesitancy and pandemic chaos, is now quietly pouring money into a future many assumed it never believed in. It’s either a radical pivot or a masterclass in political rebranding. Or perhaps it’s something stranger.

Because the word universal doesn’t just imply scope. It implies control. A solution so sweeping, so absolute, it edges past medicine into ideology. A vaccine not just for one virus, but for all strains, all mutations, all future threats. It sounds like salvation—or domination—depending on who’s whispering it into your ear.

The Myth of One Shot to Rule Them All

Let’s be clear: the science is breathtaking. If successful, a universal vaccine would change the trajectory of pandemics, possibly eliminate annual flu shots, and fortify us against bioterrorism. But when politics funds science, especially with a narrative as messianic as “universal immunity,” the result isn’t always progress. Sometimes it’s mythology.

“You have to understand,” said one bioethicist off-record, “when politicians say ‘universal,’ they don’t mean what scientists mean. It’s not about efficacy—it’s about optics. The illusion of total safety.”

The same administration that publicly downplayed COVID, toyed with bleach theories, and sowed mistrust in its own CDC is now investing in a panacea? The dissonance is operatic. It begs the question: is this a redemption arc, or just the next chapter in America’s ongoing theater of control and cure?

Blueprints, Biosecurity, and the Narrative We’re Not Hearing

There’s another layer, of course—the strategic one. The vaccine investment is being funneled through what’s being called Project NextGen. It’s not just about pandemics, but about preempting the unknown. Virus X. The next SARS. The imagined enemy. And in that future-facing paranoia lies a powerful psychological currency: fear managed by preemptive action.

But who defines the next threat? And what happens when that authority starts blending scientific consensus with political convenience?

There is a glamour to the word “universal”—a kind of architectural fantasy that promises to bulletproof the species. But even in architecture, universality is an illusion. What fits all often fits no one well. And the idea of a one-size-fits-all vaccine quietly ignores the murky ethics of testing, distribution, consent, and historical medical distrust—especially in marginalized communities.

Maybe the real question isn’t whether a universal vaccine is possible. Maybe it’s whether we’re comfortable with the systems deciding what it means to be “protected.” After all, the most potent viruses don’t always come in vials—they come in stories. And some of them, like this one, are just beginning to mutate.

Explore more

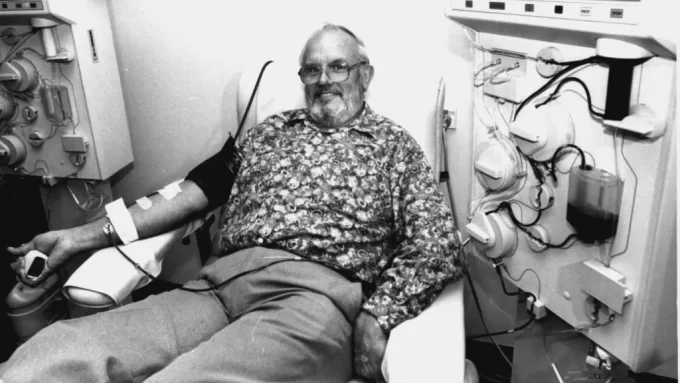

The Man Who Bled for Millions

He saved over 2.5 million babies, but no one ever recognized him...

The Silence Before the Sneeze

A dead bird, limp on the edge of a sidewalk in Guangdong,...

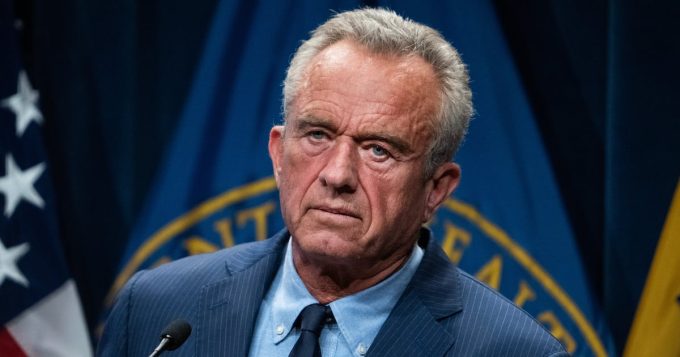

The Fetishization of Fear: RFK Jr. and the Vaccine Fetuses Lie

It begins, as these things always do, with a whisper dressed as...

The Lie That Keeps Mutating

The seduction of scandal is ancient, but its latest host is disturbingly...

Leave a comment