Weapons Don’t Kill People—Openings Do

Zach Cregger’s Weapons doesn’t just start with a bang—it starts with a fracture. One that splits the viewer’s expectations before the credits even roll.

You don’t ease into Weapons. You’re thrown—naked and nerve-first—into something sharp, sterile, and echoing with dread. The kind of opening that doesn’t introduce, but implicates. And if Zach Cregger’s Barbarian flirted with the rules of horror, Weapons seems hell-bent on disfiguring them.

The first ten minutes of the film feel like an autopsy being performed on the audience’s trust. We’re given no roadmap, no foothold—just a scene so elegant in its terror that it feels curated, almost… designed. There’s something operatic about the violence, something that suggests the real weapon isn’t what’s shown—but the structure itself.

“It’s the kind of sequence that doesn’t just set the tone,” one of the producers remarked in a recent interview, “it dares you to keep watching.” That dare is the thesis of the film. Because Weapons isn’t just horror—it’s architecture. A haunted cathedral of time loops, fragmented memories, and narrative gaslighting. And like any good cathedral, it doesn’t welcome you. It consumes you.

The Algorithm of Fear Has Evolved

This isn’t a screamfest. It’s a simulation of dread. And Cregger—now operating like a horror auteur with something to prove—knows exactly where the culture is looking and precisely where to point the mirror. Gone are the slasher tropes and final-girl formulas. What he offers instead is a story that unfolds like a psychological trapdoor: just when you think you’re safe, the floor rearranges itself.

It would be easy to compare Weapons to Ari Aster’s Hereditary or David Lynch’s Lost Highway, but that would be missing the point. Weapons isn’t referencing horror. It’s rewriting its grammar. The opening alone hints at this—a scene so jarringly out of context, it becomes a kind of anti-spoiler. You can’t tell anyone what happens because you don’t know what you just saw.

This is horror not as shock, but as seduction. An invitation to lose your bearings, then question why you needed them in the first place.

What the Eye Forgets, the Mind Replays

There’s an unnerving cleanliness to the way Weapons treats violence—not as spectacle, but as residue. By the time the credits arrive, the real story has already started, buried somewhere beneath your interpretation. And that’s what lingers. Not the blood. Not the screams. But the overwhelming sense that something has been taken from you without your consent.

That feeling is not an accident. It’s craft. Cregger, now stepping fully into his role as one of horror’s most cerebral showmen, is less interested in scaring you than in disorienting you. To him, the real horror isn’t death. It’s ambiguity.

You leave the opening scene of Weapons not knowing what just happened—but knowing it mattered. And isn’t that the most dangerous kind of cinema?

A weapon can be anything, after all. A lie. A memory. An opening so brutal, it steals your breath before you even realize it’s begun.

And isn’t that how all the best horror stories start? Not with fear, but with forgetting.

Explore more

Pianist Omar Harfouch Brings Celebrated Figures Together for a Night of Cultural Exchange – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Omar Harfouch On February 20, 2026, pianist and cultural figure...

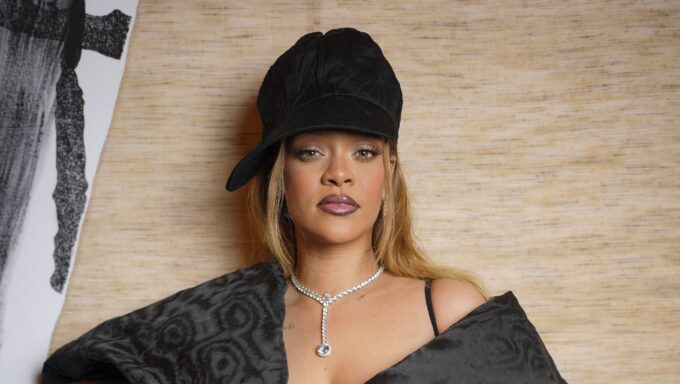

Who Is Ivana Lisette Ortiz? About the Rihanna Home Shooting Suspect – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images The suspect in the March 8,...

How Much Money Does She Have Now? – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: WWD via Getty Images Rihanna may be known as one...

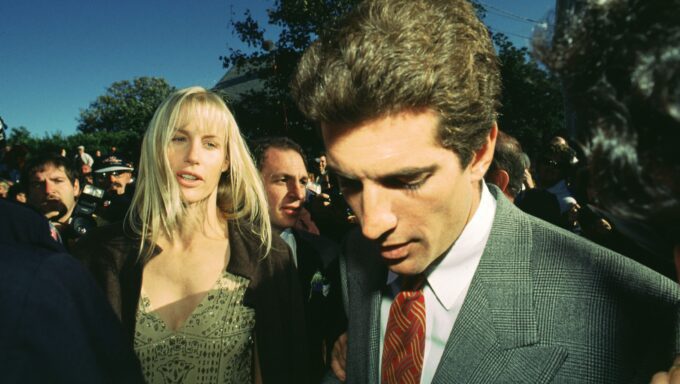

Stars Who Slammed ‘Love Story: JFK Jr. & Carolyn Bessette’: Statements – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images FX’s Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and...

Leave a comment