The $500 Million Shot in the Dark

The U.S. government is quietly preparing to pour half a billion dollars into “universal” vaccines—but the story isn’t just about science. It’s about control, memory, and the secrets that follow pandemics like shadows.

They’re calling it the “universal vaccine” now—a word so sweeping, so strange, it feels more like something out of speculative fiction than federal funding. But this isn’t a whisper in the hallways of sci-fi conventions. It’s a $500 million initiative, quietly in motion, designed not to fight a virus we know—but the one we haven’t met yet.

This week, tucked between headlines of celebrity divorces and economic forecasts, emerged a single, slippery detail: the U.S. government is quietly mobilizing a vaccine arsenal for the unknown. It sounds like foresight. It also sounds like a confession.

A Future We Secretly Expect

We don’t invest in ghosts unless we’ve already seen them. The White House’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) is partnering with private pharmaceutical companies to chase the holy grail of immunization: a shot that can target entire virus families—coronaviruses, influenzas, even filoviruses like Ebola. One vaccine to rule them all.

It begs the question: what exactly are they expecting?

There is a word that’s being passed around in biosecurity circles now: “inevitability.” As if pandemics are no longer accidents of nature, but recurring features of an age defined by interconnection, interference, and possibly—intent. “We’ve learned from COVID,” one senior official said off the record, “but not everything we learned has been made public.”

Which part of that statement feels more dangerous—the learning, or the silence?

Memory Is a Fragile Inoculation

We’ve been here before. A crisis, followed by urgency, followed by amnesia. But this time, the tempo has changed. The pandemic didn’t just break healthcare systems; it fractured trust, rewired timelines, and exposed the chasm between what leaders say and what they plan. Now, as the U.S. funds sweeping bio-research under a shimmering veil of preparedness, we’re left with that strange, metallic taste of déjà vu.

One scientist I spoke to called the program “a form of pre-trauma management.” Not prevention. Not cure. A managed anticipation of what’s to come. What does that say about the faith we’ve placed in modernity, when our boldest defense against extinction is a quietly-budgeted experiment?

This isn’t just about vaccines. It’s about narrative control. It’s about the shifting axis between governments and pharmaceutical powerhouses. And it’s about a public that no longer knows if it’s being protected—or played.

So the real question is no longer if a virus will come. It’s who will already have the cure when it does—and who will have to beg for it. Maybe the more universal thing isn’t the vaccine. Maybe it’s the forgetting.

Explore more

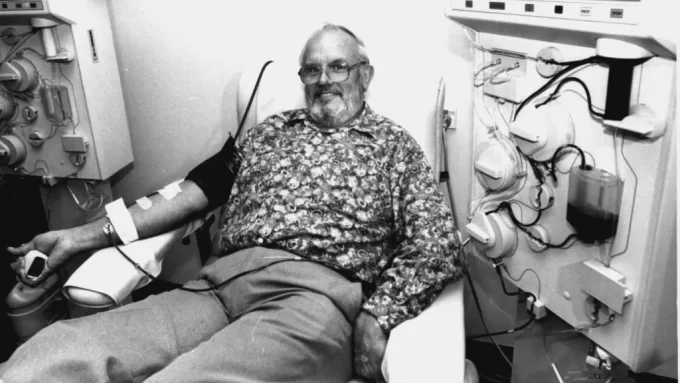

The Man Who Bled for Millions

He saved over 2.5 million babies, but no one ever recognized him...

The Silence Before the Sneeze

A dead bird, limp on the edge of a sidewalk in Guangdong,...

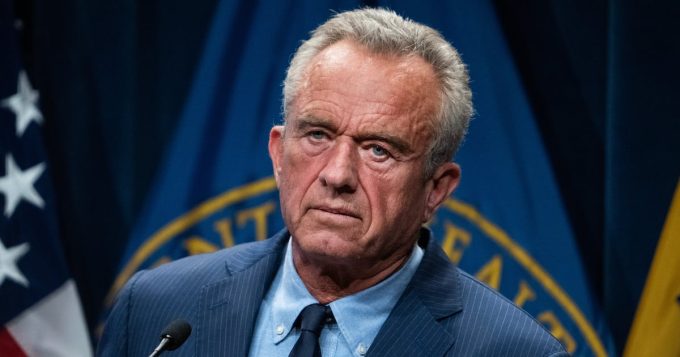

The Fetishization of Fear: RFK Jr. and the Vaccine Fetuses Lie

It begins, as these things always do, with a whisper dressed as...

The Lie That Keeps Mutating

The seduction of scandal is ancient, but its latest host is disturbingly...

Leave a comment