When Beijing Dreams in American Grit

Beijing is curating a cinematic shrine to Altman, Dogme 95, and Peckinpah—three film forces the West once feared, misunderstood, and tried to forget. So why is China remembering them now?

The lights go down in Beijing, and on the screen—a man stumbles through the desert, dust on his boots, blood in his teeth. It’s not propaganda. It’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. And it’s playing in a city that censors TikToks and blurs cleavage in reruns of Friends.

This isn’t irony. It’s something far more deliberate. This fall, China will spotlight a trio of cinematic insurgents: Robert Altman, Sam Peckinpah, and the fraying, minimalist chaos of Dogme 95. Three distinctly Western provocateurs. Three movements that once rattled the spine of Hollywood. Now, their ghosts are being resurrected halfway around the world in a country that polices its own narratives with surgical precision. So what does Beijing want with these devils?

These films don’t scream—they seethe. And we’re interested in what simmers.”

Rebellion, But Not Yours

Robert Altman’s lens was famously cluttered—overlapping dialogue, characters in constant motion, truth dripping through the cracks. Peckinpah painted violence not as spectacle, but as decay. And Dogme 95? That was cinema on its knees, stripped of vanity, raw enough to blister. None of this was made for soft consumption. None of this was ever meant to be safe.

And yet, “Art has to slip past the guards,” says an unnamed curator involved in the Beijing retrospective. “These films don’t scream—they seethe. And we’re interested in what simmers.” The statement doesn’t clarify much, but maybe that’s the point. There’s a power in screening dissent from another country. It feels like a mirror without showing your own reflection.

In a nation where the camera is still expected to behave, what does it mean to showcase the ones that never did?

Ghosts in the Projection Room

There’s something surgical in China’s choice. Altman’s America is fragmented and impersonal. Dogme’s Europe is ashamed and searching. Peckinpah’s West is suicidal. These films show a civilization unraveling—not with revolution, but rot. The censors can allow that. Because it’s not their civilization.

But what if that’s the trick? What if it’s a soft confession? A recognition, whispered between frames, that maybe no system is immune? These aren’t just old movies. They’re blueprints. For what happens when performance replaces truth, when violence is ritual, when beauty is made ugly for profit. Perhaps Beijing isn’t celebrating rebellion—they’re dissecting it.

It would be easy to call this cinema diplomacy. Easier still to write it off as hipster programming. But the selections are too specific. Too haunted. These aren’t movies you casually curate. These are messages encoded in celluloid.

Back in the theater, the projector hums. A Danish priest stares down his sins under fluorescent light. A cowboy bleeds out to a Neil Young score. Altman’s camera loses the plot. And outside, Beijing watches. Carefully. Quietly.

Because maybe the most radical thing isn’t to show these films—but to see who shows up.

Explore more

Start the New Year by Investing in Yourself – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: European Wax Center The new year is all about fresh...

Where Is Liam Conejo Ramos Now? Updates on 5-Year-Old’s ICE Detainment – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images Liam Conejo Ramos came home from preschool while...

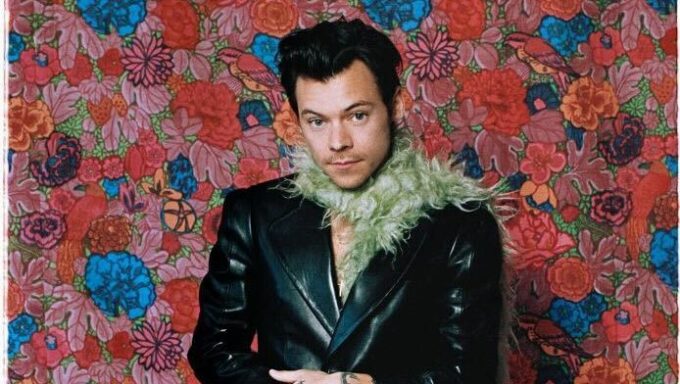

Who Is Harry Styles’ ‘Aperture’ About? Breakdown of the Lyrics – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images We’ve doing doing all this late...

When Are the Oscars 2026? Date of the Academy Awards – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images The Oscars are officially on the...

Leave a comment