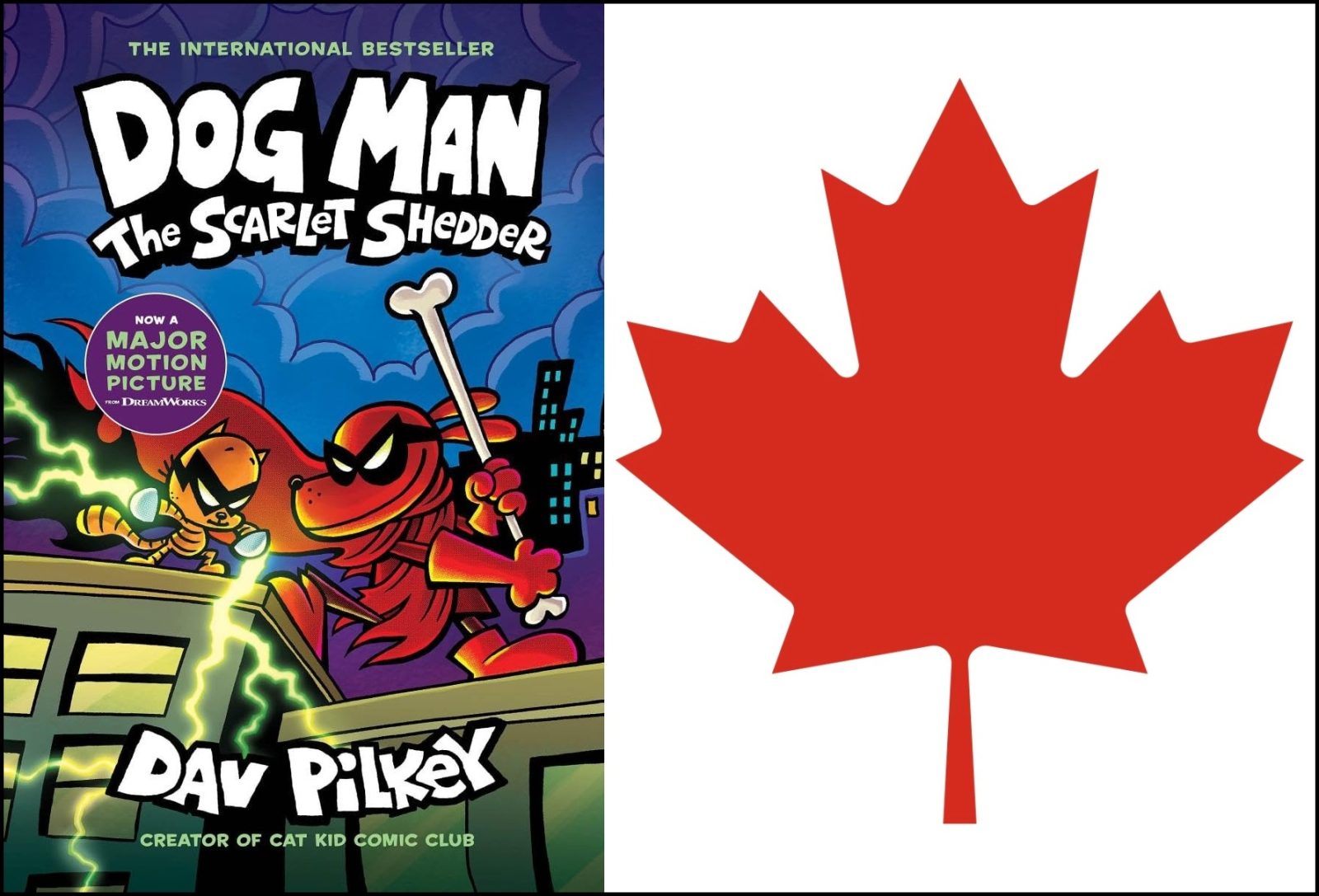

Why Is Canada Obsessed with a Crime-Fighting Dog?

Dav Pilkey’s Dog Man series didn’t just top Canada’s 2024 bestseller charts—it dominated. What does it say about us when a cartoon dog outpaces every literary heavyweight, and why can’t we look away?

A half-dog, half-cop cartoon character with a nose for justice has become Canada’s most purchased literary figure—and no one knows quite how to explain it. In a year riddled with political memoirs, feminist manifestos, and dystopian forecasts for the climate and the soul, it was Dog Man: The Scarlet Shedder that towered above them all, wagging its tail smugly from the summit of the bestseller list.

The numbers don’t lie: Dav Pilkey’s creation didn’t just perform well—it eclipsed the competition. But this isn’t merely about book sales. It’s about mood, about desire, about what an entire country reaches for when the world feels a little too complex. In a cultural climate of burnouts and breakdowns, Dog Man is more than a joke—it’s a mirror.

The Power of the Innocently Absurd

There is, of course, something irresistible about Pilkey’s art of deliberate chaos. His stories don’t follow rules. They erupt. The pacing is frenetic, the humor anarchic, the language playfully blunt. And in that hurricane of scribbles and silliness lies something oddly intimate—relief. “Kids love these books because they feel like freedom,” one Toronto bookseller noted. “Adults buy them because they remember what that freedom felt like.”

While critics debate the literary merit of graphic novels, Pilkey’s impact is undeniable. He’s built a universe where trauma is transformed into slapstick, justice comes with punchlines, and villains get therapy. In a world spiraling toward seriousness, the Dog Man phenomenon reads like a collective, cartoonish exhale. It isn’t escapism—it’s resistance in disguise.

What the Bestseller List Won’t Tell You

Yet behind the joyful absurdity, there’s an undertone of cultural fatigue. Pilkey’s popularity reveals a mass craving for stories that ask nothing of us except to smile. No metaphors to unravel. No darkness to trudge through. Just a good dog doing his best. In an era where intellectual capital is currency, that’s a radical proposition.

And then there’s the irony—our most purchased author in 2024 isn’t Canadian, nor particularly highbrow, nor even consciously chasing legacy. Pilkey writes from the heart, for kids, for misfits, for readers who’d rather laugh than decode. And that might be the biggest provocation of all: a bestseller list headlined by someone who doesn’t play the literary game, yet wins it every year.

So where does that leave us? With a question that’s less about Pilkey and more about us: when did we stop wanting stories that challenged us—and start needing ones that simply loved us?

Explore more

When “107 Days” Meets Outcry: Harris’s Book Tour Interrupted

The microphone crackled to life, and before Harris could finish her opening...

Whispers in the Shadows: Why Holly Black’s Sequel Is a Dark Invitation We Can’t Ignore

The night isn’t just dark—it’s ravenous, greedy, and it’s coming for you....

Why Stephenie Meyer’s Regret About Edward Changes Everything You Thought You Knew

The moment Stephenie Meyer admitted she wouldn’t pick Edward Cullen today, a...

When Fear, Fury & Feathers Collide: Cinema, Superheroes, and a Confessional Album

Open with tension—the kind that threads through a scream, a reveal, and...

Leave a comment