Frankenstein Rebuilt: del Toro’s Haunted Legacy Beckons

Guillermo del Toro says Frankenstein wasn’t just a film—it was therapy, forged by his father’s kidnapping and a late reconciliation; what if creation itself is a search for absolution?

A director revisits his greatest dream—not to conjure monsters, but to exorcise his own. Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein rises, bathed in the shadow of his father’s kidnapping, transformed not by horror, but by the quiet redemption that only forgiveness can forge. Isn’t it strange—how trauma hides within myth, waiting to be untangled?

Here is a film born not from spectacle but from survival—where the grudge that imprisoned del Toro and his father becomes the central paradox of creation. Ponder the tension between creation and reconciliation, and consider what monsters we still carry inside.

Forgiveness as Liberation

In Toronto, del Toro revealed a truth that tilts the gothic tale on its head: “A grudge takes two prisoners,” he said, “and forgiveness liberates two people.” Suddenly, Victor’s tormented mind and the Creature’s agony echo not just gothic horror, but the songs of broken bonds and delayed reconciliation. When he finally sat with his father and heard the untold story, the film shifted—from regret to release.

This is Frankenstein not as tragedy, but as confession.

When Monsters Mirror Our Longing

Oscar Isaac inhabits Victor as a rock-star of neurosis—fragile, brilliant, unraveling under the weight of a domineering father. The Creature (Jacob Elordi) emerges not as pure evil, but a fragile marble echo of abandonment and longing. Del Toro doesn’t divide their narratives into two films as once intended. Instead, he mirrors them—creator and creation, bound in trauma, reflection, and the hope for parental mercy.

Here, practical effects aren’t nostalgia—they’re human texture. Christoph Waltz drily blessed them: “CGI is for losers.” In that dismissal lies the film’s intent—to feel, not just to frighten.

This is no standard retelling—it’s an elegy and an awakening. So, what happens when our deepest fears become our greatest teachers?

Explore more

Start the New Year by Investing in Yourself – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: European Wax Center The new year is all about fresh...

Where Is Liam Conejo Ramos Now? Updates on 5-Year-Old’s ICE Detainment – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: Getty Images Liam Conejo Ramos came home from preschool while...

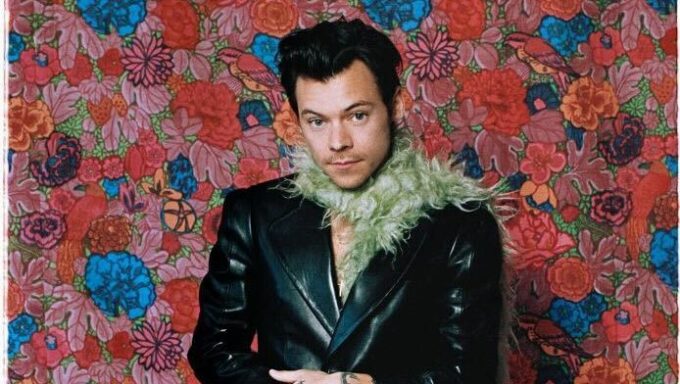

Who Is Harry Styles’ ‘Aperture’ About? Breakdown of the Lyrics – Hollywood Life

View gallery Image Credit: Getty Images We’ve doing doing all this late...

When Are the Oscars 2026? Date of the Academy Awards – Hollywood Life

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images The Oscars are officially on the...

Leave a comment